Text vorlesen lassen

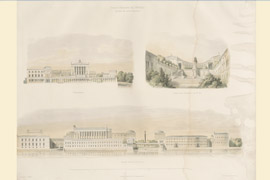

A masterplan for a "Sanctuary for Art and Science"

After more than 40 years in power, Friedrich Wilhelm III died on 7 June 1840. The Crown Prince had waited a long time to finally be able to initiate all the building projects in which he hopes to manifest his conservative concept of Prussia and history for eternity.

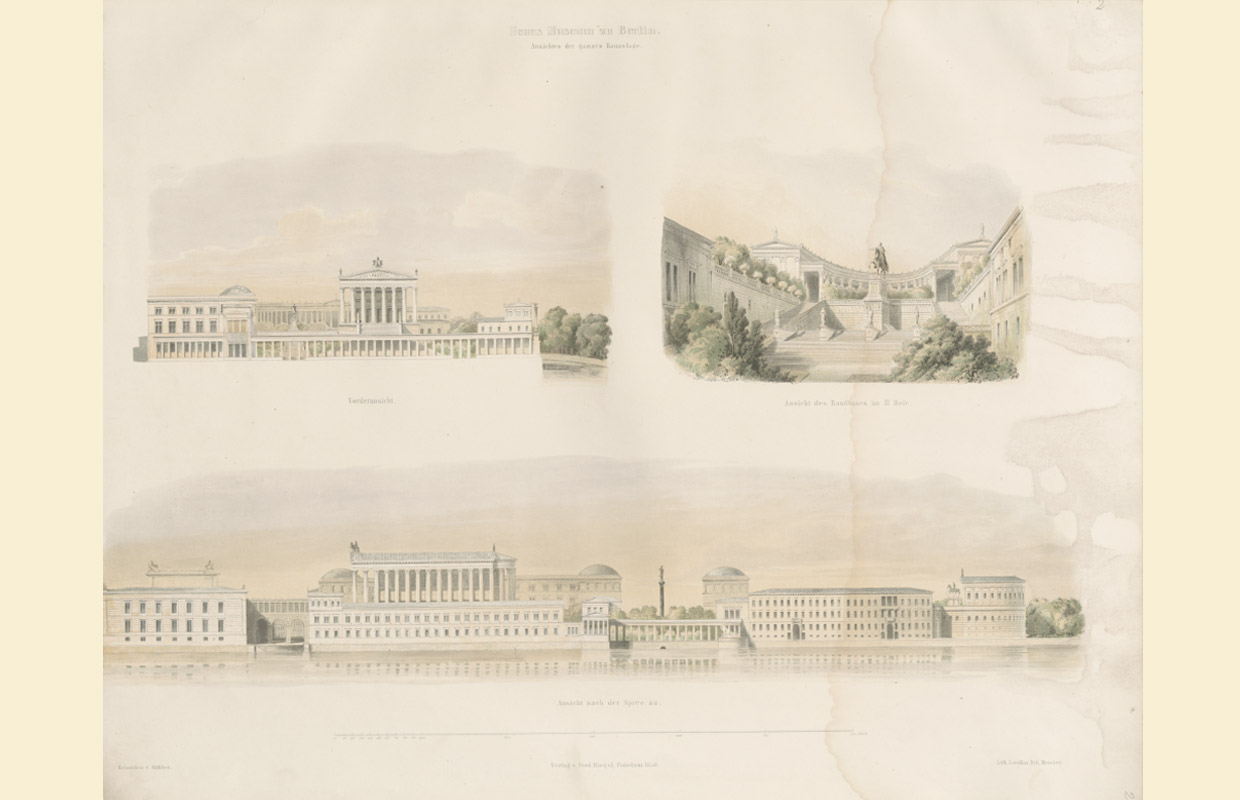

Probably the most important of these projects was the remodelling of the entire northern Spree island behind Schinkel's museum, which had opened in 1830, into a "quiet, richly endowed sanctuary for art and science". In 1840, Friedrich Wilhelm IV (1795-1861) commissioned Ignaz v. Olfers (1793-1871), Director General of the Royal Museums, to develop a concept for this.

Instead of Schinkel, who had suffered several strokes in September 1840 and was facing death with impaired vision and speech, his pupil Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865) was involved in the design. In June 1841, Stüler and Olfers presented their masterplan. Two of the proposed buildings were actually realised - the Neues Museum and the Nationalgalerie.

A masterplan for a "Sanctuary for Art and Science"

After more than 40 years in power, Friedrich Wilhelm III died on 7 June 1840. The Crown Prince had waited a long time to finally be able to initiate all the building projects in which he hopes to manifest his conservative concept of Prussia and history for eternity.

Probably the most important of these projects was the remodelling of the entire northern Spree island behind Schinkel's museum, which had opened in 1830, into a "quiet, richly endowed sanctuary for art and science". In 1840, Friedrich Wilhelm IV (1795-1861) commissioned Ignaz v. Olfers (1793-1871), Director General of the Royal Museums, to develop a concept for this.

Instead of Schinkel, who had suffered several strokes in September 1840 and was facing death with impaired vision and speech, his pupil Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865) was involved in the design. In June 1841, Stüler and Olfers presented their masterplan. Two of the proposed buildings were actually realised - the Neues Museum and the Nationalgalerie.

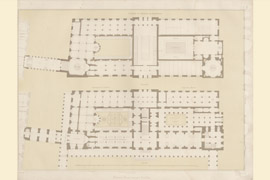

Architecture and construction visualise the cultural history of mankind

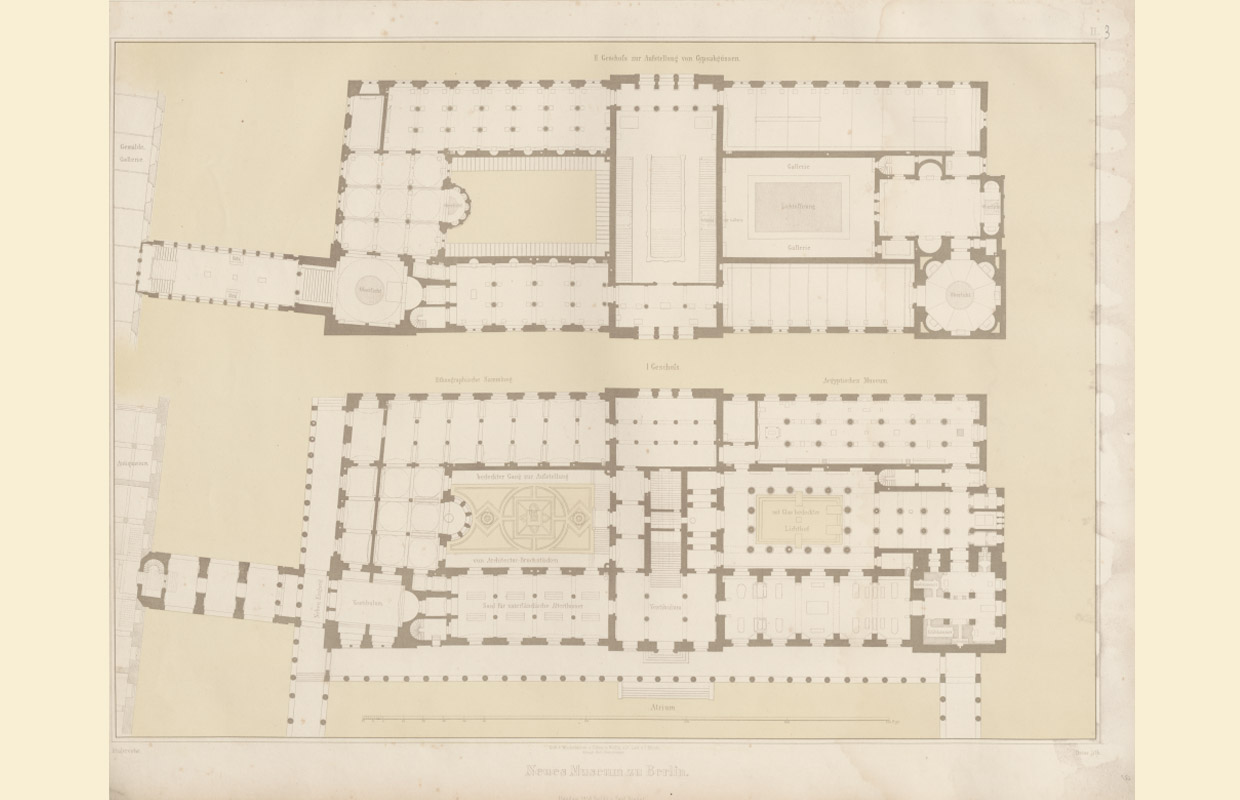

Like Schinkel for the Altes Museum, Stüler also envisaged a four-wing complex with two inner courtyards for the Neues Museum. Instead of two, there are now three main storeys. Above all, however, instead of the rotunda there is a magnificent staircase hall in the centre; some architectural historians consider it to be the best staircase of late classicism, even one of the best architectural creations of that era.

According to Stüler's ideas, by ascending the staircase, one is supposed to walk through the cultural history of mankind - from the massive mythological beginnings in the basement to the ornate art chambers of the present day.

The architecture and construction visualise this ideal of progress in the sequence of the three main storeys (here the plinth and first floor). In the south wing (left), the material of the columns changes from heavy stone to slender cast iron; in the north wing, column-free halls open up in the upper storeys, spanned by previously unknown filigree iron trusses.

Architecture and construction visualise the cultural history of mankind

Like Schinkel for the Altes Museum, Stüler also envisaged a four-wing complex with two inner courtyards for the Neues Museum. Instead of two, there are now three main storeys. Above all, however, instead of the rotunda there is a magnificent staircase hall in the centre; some architectural historians consider it to be the best staircase of late classicism, even one of the best architectural creations of that era.

According to Stüler's ideas, by ascending the staircase, one is supposed to walk through the cultural history of mankind - from the massive mythological beginnings in the basement to the ornate art chambers of the present day.

The architecture and construction visualise this ideal of progress in the sequence of the three main storeys (here the plinth and first floor). In the south wing (left), the material of the columns changes from heavy stone to slender cast iron; in the north wing, column-free halls open up in the upper storeys, spanned by previously unknown filigree iron trusses.

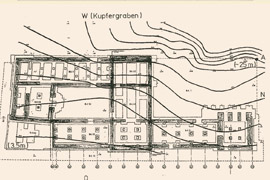

A difficult subsoil – lightweight construction as the answer

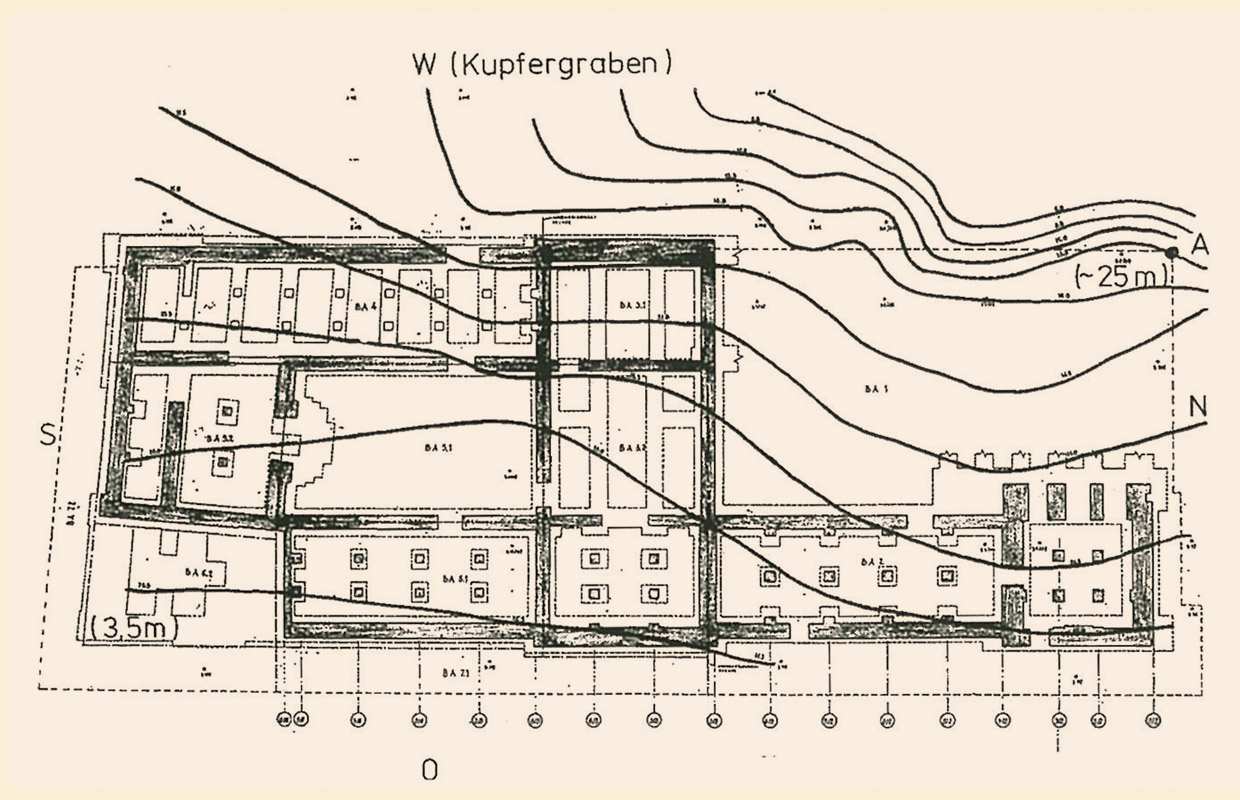

The main technical challenge for the construction lies in the extremely difficult foundation situation. Here, in the former Berlin glacial valley, the generally well-supporting subsoil of glacial sands is repeatedly interspersed with non-load-bearing scours filled with organic inclusions that were washed out in the glacial riverbed.

The Neues Museum is even more affected by this than the Altes Museum. The load-bearing subsoil, which lies at a depth of around 3.50 metres deep at the south-east corner, falls away to the north-west to a depth of almost 25 metres (shown here for the plans to rebuild the post-war ruins).

In order to still be able to build here, not only a pile grid is indispensable. The structure as a whole had to be as light as possible. The solution of Stüler and his construction managers is a structural programme that is consistently oriented towards the principle of lightweight construction, right down to the details of the supporting structure and materials.

A difficult subsoil – lightweight construction as the answer

The main technical challenge for the construction lies in the extremely difficult foundation situation. Here, in the former Berlin glacial valley, the generally well-supporting subsoil of glacial sands is repeatedly interspersed with non-load-bearing scours filled with organic inclusions that were washed out in the glacial riverbed.

The Neues Museum is even more affected by this than the Altes Museum. The load-bearing subsoil, which lies at a depth of around 3.50 metres deep at the south-east corner, falls away to the north-west to a depth of almost 25 metres (shown here for the plans to rebuild the post-war ruins).

In order to still be able to build here, not only a pile grid is indispensable. The structure as a whole had to be as light as possible. The solution of Stüler and his construction managers is a structural programme that is consistently oriented towards the principle of lightweight construction, right down to the details of the supporting structure and materials.

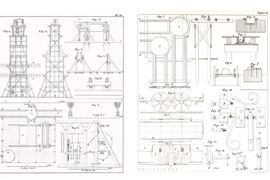

Steam power and iron railways - rethinking the construction process

The demolition of existing buildings and excavation of the building pit begins as early as June 1841. On 11 September, the first of a total of 2,344 piles is driven into the ground. Construction of the building can start in 1843. The foundation stone is laid on 6 April, and by the end of the year the shell of the building is largely completed.

The astonishing construction progress is made possible by a completely new way of organising the building process, which is a quantum leap in Prussian construction technology. Even the piles have been driven by steam power for the first time; the latter is then also used for dewatering and for operating the mortar mixers.

A railway network is installed on the construction site, on which the building materials are brought from the Spree canal and distributed in specially constructed lorries. Vertical transport is provided by a 38-metre-high, steam-powered lift in the area of the future main staircase. Lorries weighing up to 5 tonnes are lifted to each floor of the building shell without reloading, where they can be further distributed again on rails.

Steam power and iron railways - rethinking the construction process

The demolition of existing buildings and excavation of the building pit begins as early as June 1841. On 11 September, the first of a total of 2,344 piles is driven into the ground. Construction of the building can start in 1843. The foundation stone is laid on 6 April, and by the end of the year the shell of the building is largely completed.

The astonishing construction progress is made possible by a completely new way of organising the building process, which is a quantum leap in Prussian construction technology. Even the piles have been driven by steam power for the first time; the latter is then also used for dewatering and for operating the mortar mixers.

A railway network is installed on the construction site, on which the building materials are brought from the Spree canal and distributed in specially constructed lorries. Vertical transport is provided by a 38-metre-high, steam-powered lift in the area of the future main staircase. Lorries weighing up to 5 tonnes are lifted to each floor of the building shell without reloading, where they can be further distributed again on rails.

Iron all around

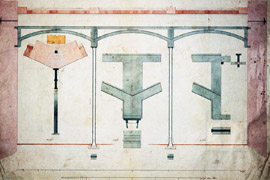

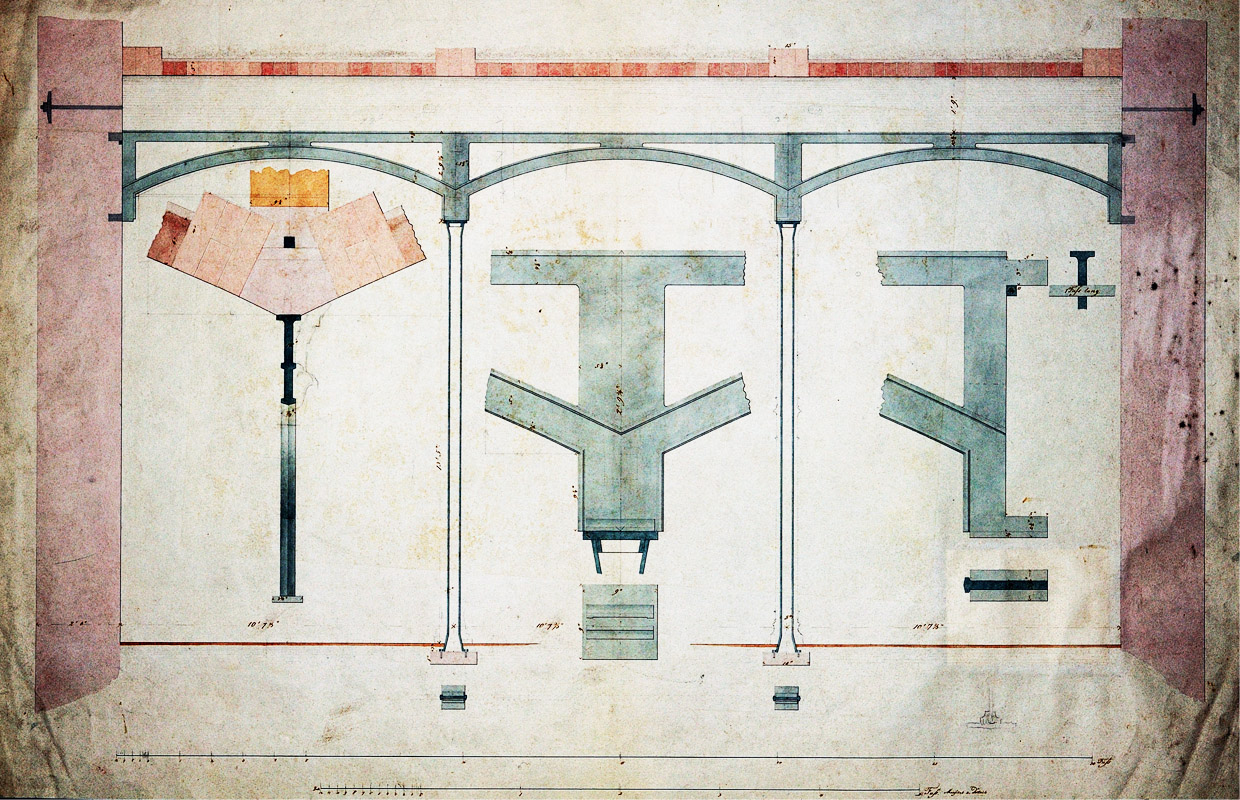

The use of iron components makes a decisive contribution both to the realisation of the "principle of lightweight construction" and to speeding up the construction process. They run through the entire structure, many of them concealed in the walls and ceilings. Today, only some of them remain, such as the cast-iron support frames for the art chambers on the upper floor shown here in the contemporary work drawing.

Iron all around

The use of iron components makes a decisive contribution both to the realisation of the "principle of lightweight construction" and to speeding up the construction process. They run through the entire structure, many of them concealed in the walls and ceilings. Today, only some of them remain, such as the cast-iron support frames for the art chambers on the upper floor shown here in the contemporary work drawing.

1843: Things have to be done quickly - the vaulting is realised later

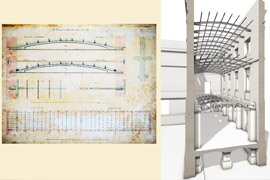

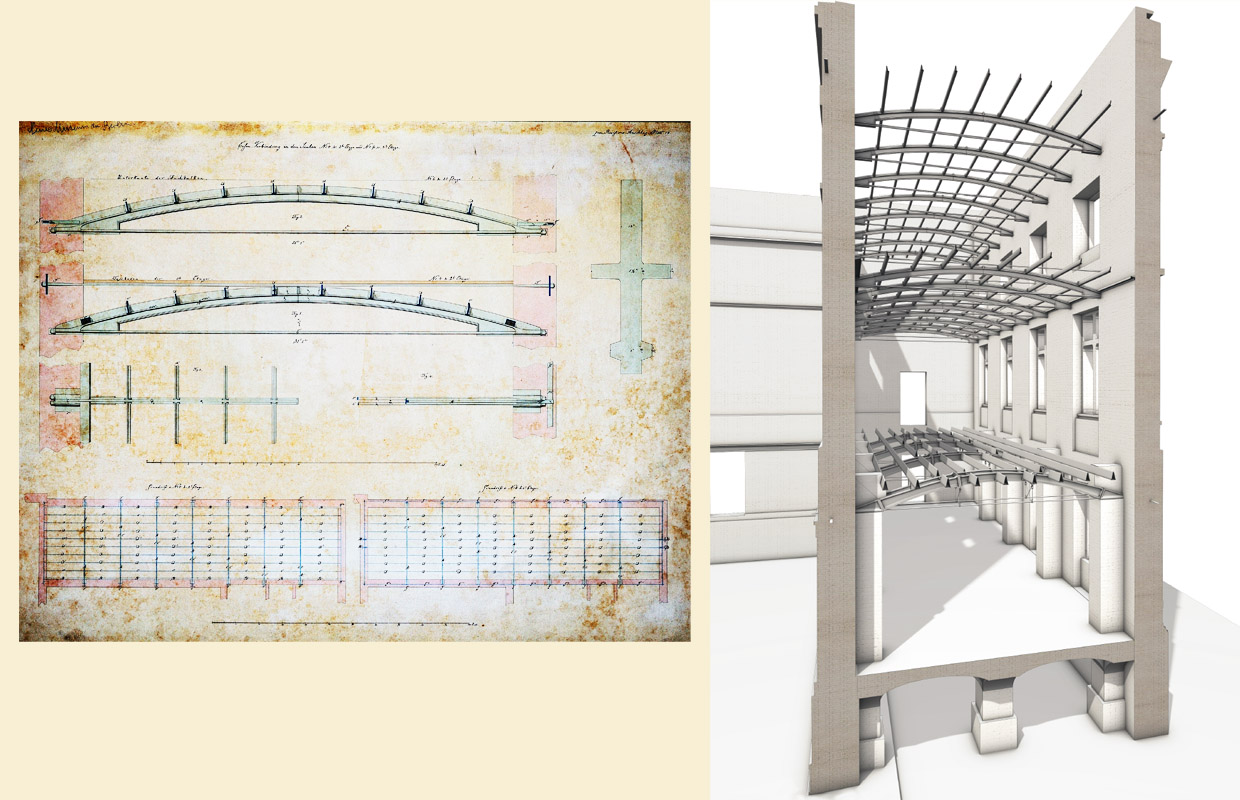

Probably the most impressive of the iron structures are the "bowstring girders", which span the large halls in the two northern wings with widths of around 10 metres without supports.

It is precisely these that help to complete the shell construction in such a short time: In June, August and October 1843, the prefabricated beams for all three ceilings are delivered and installed at the same time as the outer walls are being raised. They stiffen the outer walls without wasting time closing the ceilings; the vaulting will not begin until the following year.

The state of construction of the two north wings reached at the end of 1843 as a sensation. Nothing like it has ever been seen before in Berlin or Prussia: a three-storey high hollow building, structured and stiffened solely by three iron girder grids.

1843: Things have to be done quickly - the vaulting is realised later

Probably the most impressive of the iron structures are the "bowstring girders", which span the large halls in the two northern wings with widths of around 10 metres without supports.

It is precisely these that help to complete the shell construction in such a short time: In June, August and October 1843, the prefabricated beams for all three ceilings are delivered and installed at the same time as the outer walls are being raised. They stiffen the outer walls without wasting time closing the ceilings; the vaulting will not begin until the following year.

The state of construction of the two north wings reached at the end of 1843 as a sensation. Nothing like it has ever been seen before in Berlin or Prussia: a three-storey high hollow building, structured and stiffened solely by three iron girder grids.

1845: Finishing work begins, but will still take a long time

By 1845, all the ceilings have been vaulted, the last of the iron support structures have been erected on the upper floors and all the exterior walls have been plastered. And yet it will still be many years before the building is finally opened.

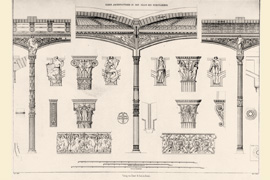

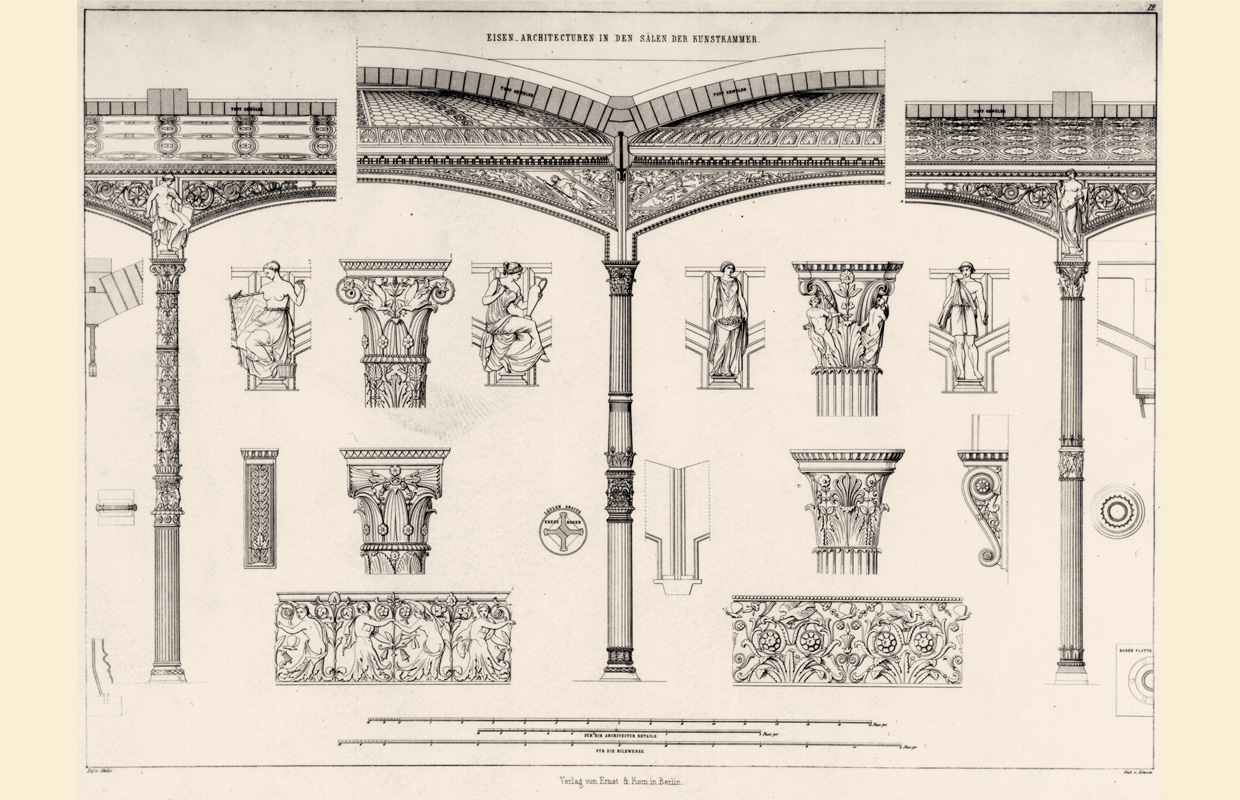

The finishing of the building is complex and extremely costly, ranging - from the installation of a centrally operated air heating system to the large-scale, yet artistically high-quality wall paintings and the "ennobling" of the raw iron structures with zinc and other panelling, shown here for the art chambers. External factors such as strikes around the revolutionary year of 1848 also hamper construction progress.

Last but not least, even before the building is completed, it becomes apparent that Stüler has assessed the situation of the load-bearing foundation soil too favourably at the time. Misjudging the true depth of the scour of up to 25 metres, he has set the pile length at a maximum of 58 feet (approx. 18 metres) – a decision that has proved to be a fatal error in the north-western part of the construction area as early as the 1850s, with clear settlement cracks and the need for first securing measures.

1845: Finishing work begins, but will still take a long time

By 1845, all the ceilings have been vaulted, the last of the iron support structures have been erected on the upper floors and all the exterior walls have been plastered. And yet it will still be many years before the building is finally opened.

The finishing of the building is complex and extremely costly, ranging - from the installation of a centrally operated air heating system to the large-scale, yet artistically high-quality wall paintings and the "ennobling" of the raw iron structures with zinc and other panelling, shown here for the art chambers. External factors such as strikes around the revolutionary year of 1848 also hamper construction progress.

Last but not least, even before the building is completed, it becomes apparent that Stüler has assessed the situation of the load-bearing foundation soil too favourably at the time. Misjudging the true depth of the scour of up to 25 metres, he has set the pile length at a maximum of 58 feet (approx. 18 metres) – a decision that has proved to be a fatal error in the north-western part of the construction area as early as the 1850s, with clear settlement cracks and the need for first securing measures.

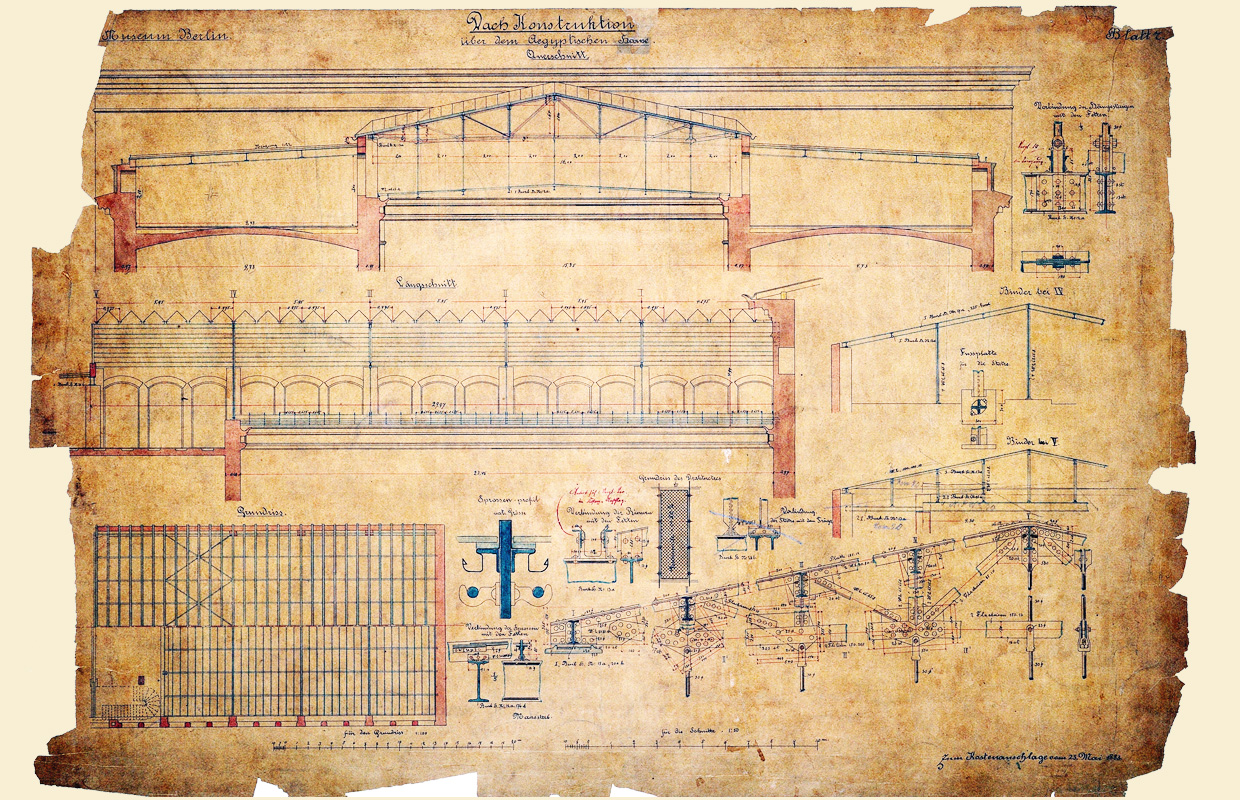

1883/84: New trussed girders on the inner courtyards

It is not until 1859 that the Ethnographic Collection is opened as the last department of the Neues Museum.

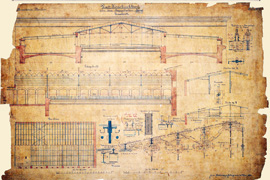

In the following decades, the museum is repeatedly remodelled. In the 1880s, for example, the flat roof spaces are converted into an additional usable mezzanine floor. The inner courtyard walls are raised, windows are added and the inclination of the monopitch roofs - previously inwards - is now turned outwards.

As a result, the glass and iron roof over the Egyptian Courtyard, developed by August Borsig in the 1840s and spectacular in its day, has to make way for a new steel framework. The surviving original drawing shows the planning status from 1883.

1883/84: New trussed girders on the inner courtyards

It is not until 1859 that the Ethnographic Collection is opened as the last department of the Neues Museum.

In the following decades, the museum is repeatedly remodelled. In the 1880s, for example, the flat roof spaces are converted into an additional usable mezzanine floor. The inner courtyard walls are raised, windows are added and the inclination of the monopitch roofs - previously inwards - is now turned outwards.

As a result, the glass and iron roof over the Egyptian Courtyard, developed by August Borsig in the 1840s and spectacular in its day, has to make way for a new steel framework. The surviving original drawing shows the planning status from 1883.

Around 1910: Exacerbated subsidence damage

In the 1910s, the extensive foundation work for the new Pergamonmuseum exacerbate the subsidence damages of the immediately neighbouring Neues Museum. In the area of the Egyptian Courtyard, tie rods are installed underneath the basement floor to brace the endangered areas with the staircase.

Other areas remain largely untouched, such as the western art chamber (Kunstkammersaal), shown here in a photograph presumably from the 1920s.

Around 1910: Exacerbated subsidence damage

In the 1910s, the extensive foundation work for the new Pergamonmuseum exacerbate the subsidence damages of the immediately neighbouring Neues Museum. In the area of the Egyptian Courtyard, tie rods are installed underneath the basement floor to brace the endangered areas with the staircase.

Other areas remain largely untouched, such as the western art chamber (Kunstkammersaal), shown here in a photograph presumably from the 1920s.

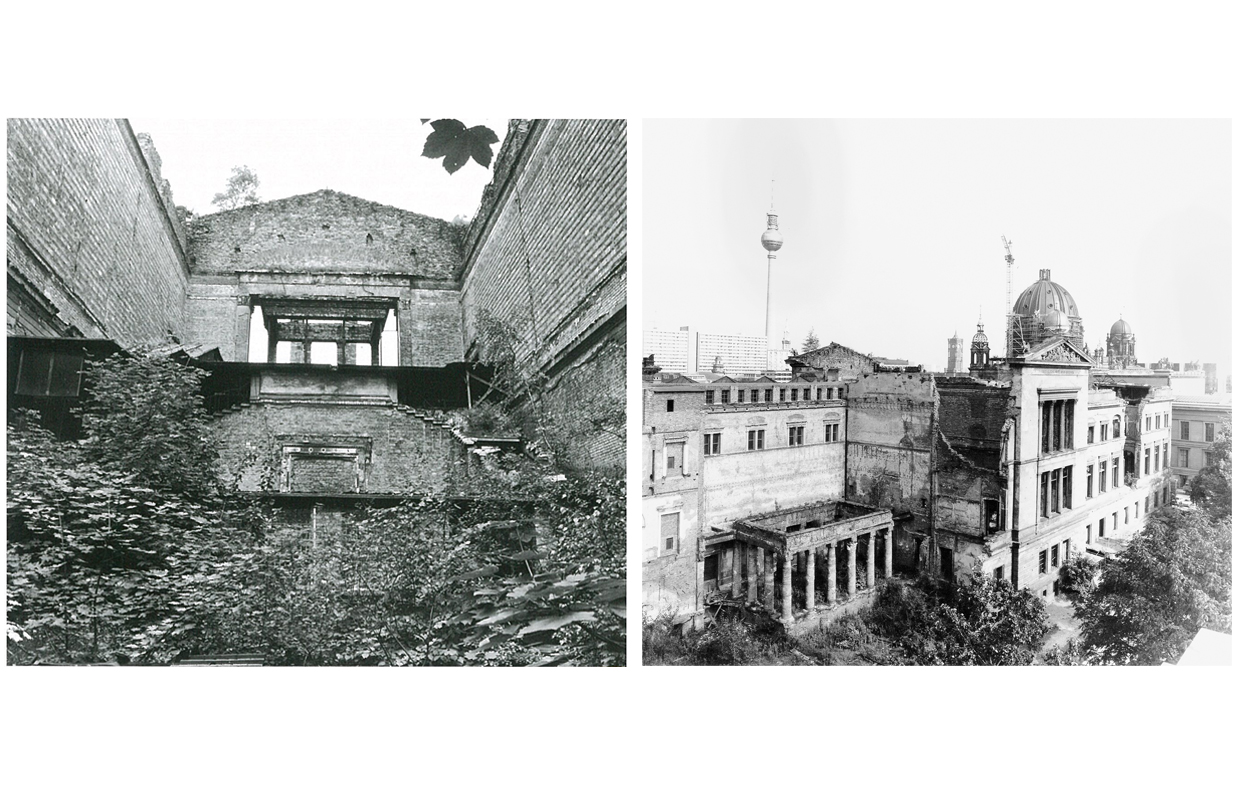

1943-45: The stairwell and the north-west wing are destroyed

Like the other buildings on Museum Island, the Neues Museum is closed immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, and significant parts of the museum's collection are removed from storage.

In the night from 23 to 24 November 1943 - exactly 100 years after the shell of the building was completed - the first heavy bomb hits occurre; the main staircase burns out completely. In the last major air raid on Berlin's city centre on 3 February 1945, which also seales the fate of the Altes Museum, high explosive bombs destroy large areas around the Egyptian courtyard (Ägyptischer Hof). In April 1945, direct shelling hits the once magnificent building one last time.

1943-45: The stairwell and the north-west wing are destroyed

Like the other buildings on Museum Island, the Neues Museum is closed immediately after the German invasion of Poland in 1939, and significant parts of the museum's collection are removed from storage.

In the night from 23 to 24 November 1943 - exactly 100 years after the shell of the building was completed - the first heavy bomb hits occurre; the main staircase burns out completely. In the last major air raid on Berlin's city centre on 3 February 1945, which also seales the fate of the Altes Museum, high explosive bombs destroy large areas around the Egyptian courtyard (Ägyptischer Hof). In April 1945, direct shelling hits the once magnificent building one last time.

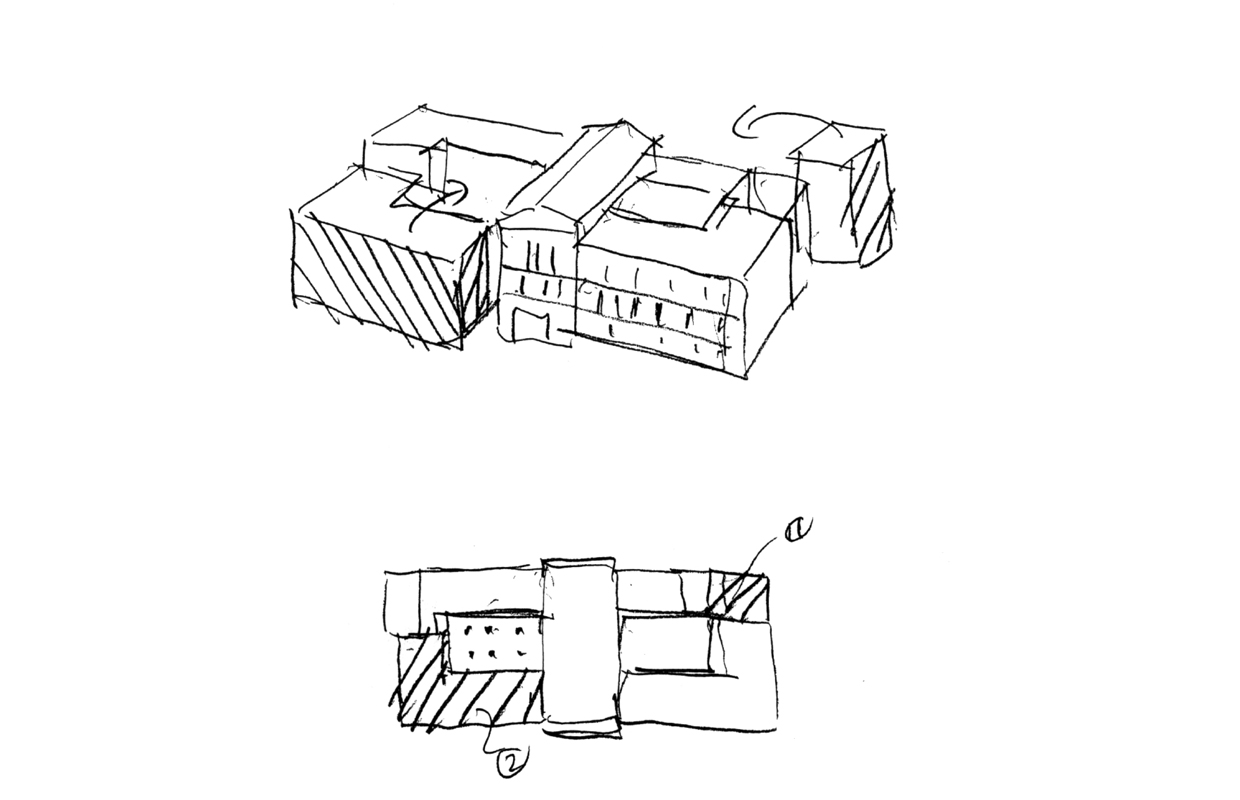

"Complementary restoration" as a principle for reconstruction

After 1945, the ruins, which have only been partially destroyed, remained relatively unprotected from the weather and looting for decades, despite initial safety measures and dedicated efforts by the State Museums of the GDR.

It is not until the end of 1985 that the decision is made in favour of general reconstruction. Large-scale salvage and safety measures finally begin, and detailed plans are drawn up for a complete replacement foundation. On 1 September 1989, 50 years after the outbreak of the Second World War, the foundation stone is ceremoniously laid and the first new bored pile is installed.

A good two months later, the Wall falls. In re-unified Berlin the concept of a largely true to original reconstruction that has been planned until then is fundamentally called into question. At the end of 1997, David Chipperfield's completely different concept of a "supplementary reconstruction" (here in an early sketch) finally emerges as the winner of two consecutive competitions: From then on, reconstruction will not be characterised by reconstruction, but by preserving, supplementing and building on.

"Complementary restoration" as a principle for reconstruction

After 1945, the ruins, which have only been partially destroyed, remained relatively unprotected from the weather and looting for decades, despite initial safety measures and dedicated efforts by the State Museums of the GDR.

It is not until the end of 1985 that the decision is made in favour of general reconstruction. Large-scale salvage and safety measures finally begin, and detailed plans are drawn up for a complete replacement foundation. On 1 September 1989, 50 years after the outbreak of the Second World War, the foundation stone is ceremoniously laid and the first new bored pile is installed.

A good two months later, the Wall falls. In re-unified Berlin the concept of a largely true to original reconstruction that has been planned until then is fundamentally called into question. At the end of 1997, David Chipperfield's completely different concept of a "supplementary reconstruction" (here in an early sketch) finally emerges as the winner of two consecutive competitions: From then on, reconstruction will not be characterised by reconstruction, but by preserving, supplementing and building on.

The historic structures aren't being replaced, but left as load-bearing

The safeguarding and restoration of the remaining parts that is now required also includes the historic load-bearing structure with all its peculiarities and variants.

Precisely because architecture and construction had been understood, developed and displayed as an inseparable unit in Stüler's concept, the unique structural diversity of the building must now not only be preserved. Rather, the historical load-bearing structures must be retained in their load-bearing functions for future use as far as possible - regardless of the fact that they defy today's regulations and verification concepts. The new structural engineers have to master a challenge that is not inferior to that of the 1840s.

The solutions they develop after intensive preliminary investigations have been described in detail elsewhere. Examples of this include the reconstruction of Stüler's pot vaults with new clay pots and the reinforcement of historic cast iron beams with CFRP lamellae.

The historic structures aren't being replaced, but left as load-bearing

The safeguarding and restoration of the remaining parts that is now required also includes the historic load-bearing structure with all its peculiarities and variants.

Precisely because architecture and construction had been understood, developed and displayed as an inseparable unit in Stüler's concept, the unique structural diversity of the building must now not only be preserved. Rather, the historical load-bearing structures must be retained in their load-bearing functions for future use as far as possible - regardless of the fact that they defy today's regulations and verification concepts. The new structural engineers have to master a challenge that is not inferior to that of the 1840s.

The solutions they develop after intensive preliminary investigations have been described in detail elsewhere. Examples of this include the reconstruction of Stüler's pot vaults with new clay pots and the reinforcement of historic cast iron beams with CFRP lamellae.

Pioneering for engineering in existing buildings

Today, the Neues Museum, which reopened in 2009, is one of the highlights of the World Heritage Site Museum Island in two respects: built during the first phase of Prussian industrialisation, it impressively testifies to the emergence of a new Prussian art of construction at that time. Rebuilt with great respect for the historical heritage and openness to unusual solutions, it also stands for forward-looking engineering in the existing building.

In 2014, it was honoured by the Federal Chamber of Engineers as a "Historic Landmark of Engineering Design in Germany".

Video about the Neues Museum (... scroll down, it's the 14th film!)

Pioneering for engineering in existing buildings

Today, the Neues Museum, which reopened in 2009, is one of the highlights of the World Heritage Site Museum Island in two respects: built during the first phase of Prussian industrialisation, it impressively testifies to the emergence of a new Prussian art of construction at that time. Rebuilt with great respect for the historical heritage and openness to unusual solutions, it also stands for forward-looking engineering in the existing building.

In 2014, it was honoured by the Federal Chamber of Engineers as a "Historic Landmark of Engineering Design in Germany".

Video about the Neues Museum (... scroll down, it's the 14th film!)

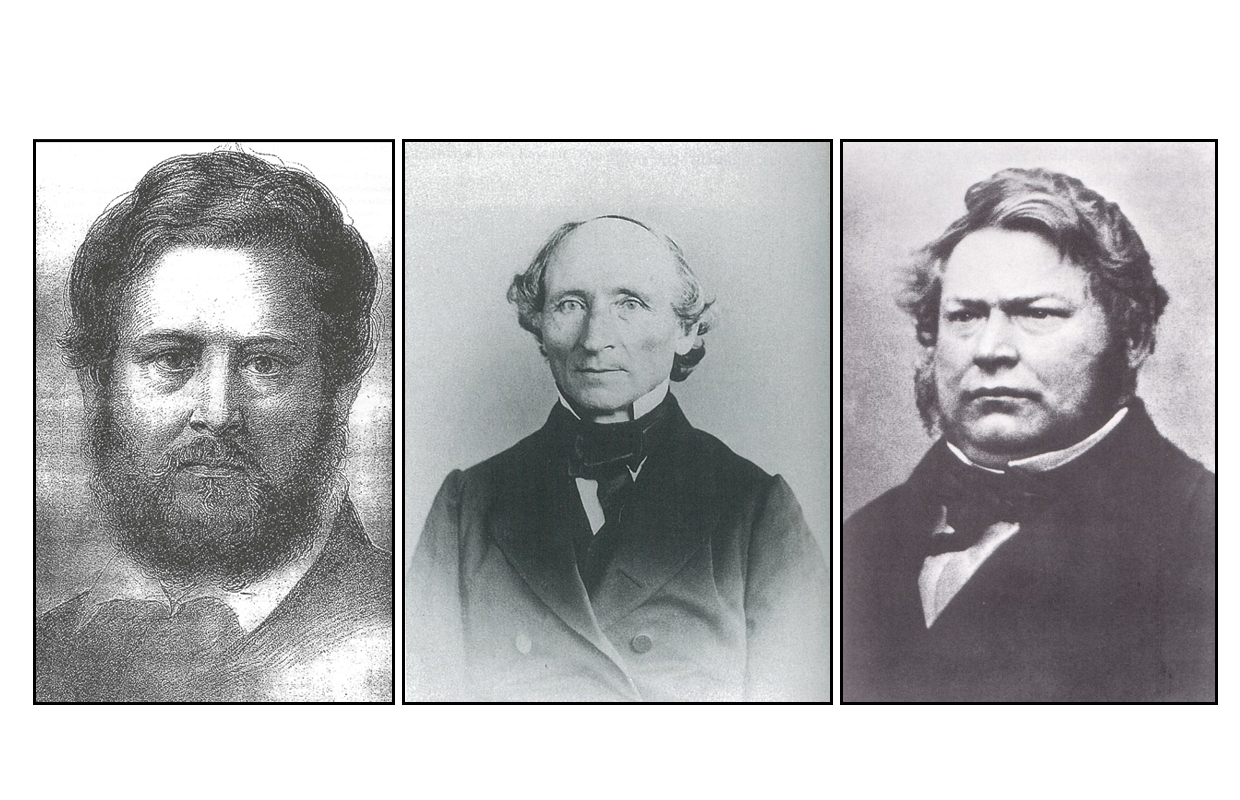

Who was responsible for the structural design?

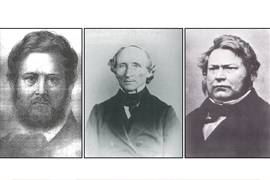

Who designed, developed and was responsible for the complex structure?

The question leads first and foremost to the little-known construction manager Carl Wilhelm Hoffmann (1810-1895). His range of activities was very similar to that of a modern-day structural engineer: Hoffmann designed, constructed, carries out tests and performed structural calculations. In 1841, he was commissioned with the "special management" and remained involved in construction until 1853.

However, Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865) certainly also made a significant contribution to the structural design. Like Schinkel, he was always dedicated to the new structural engineering options of his time. Like no other architect of the Schinkel school, he also realised other important iron buildings after the Neues Museum.

And finally, the main responsible for the iron structures must be mentioned: The expertise and creativity of the "locomotive king" August Borsig (1804-1854) made a decisive contribution to their successful realisation, particularly in terms of detailing.

Who was responsible for the structural design?

Who designed, developed and was responsible for the complex structure?

The question leads first and foremost to the little-known construction manager Carl Wilhelm Hoffmann (1810-1895). His range of activities was very similar to that of a modern-day structural engineer: Hoffmann designed, constructed, carries out tests and performed structural calculations. In 1841, he was commissioned with the "special management" and remained involved in construction until 1853.

However, Friedrich August Stüler (1800-1865) certainly also made a significant contribution to the structural design. Like Schinkel, he was always dedicated to the new structural engineering options of his time. Like no other architect of the Schinkel school, he also realised other important iron buildings after the Neues Museum.

And finally, the main responsible for the iron structures must be mentioned: The expertise and creativity of the "locomotive king" August Borsig (1804-1854) made a decisive contribution to their successful realisation, particularly in terms of detailing.

Key data

Location: Bodestraße 4, 10117 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period:

1841-59, shell 1841-45

1987-2009 securing and reconstruction

Structural design:

- Original building: Friedrich August Stüler, and Carl Wilhelm Hoffmann

- Reconstruction: Ingenieurgruppe Bauen (IGB)

Overall planning:

- Original building: Friedrich August Stüler with Ignaz Maria von Olfers

- Reconstruction: David Chipperfield Architects with Julian Harrap

Execution of construction work:

- Original construction: Numerous regional construction companies;

- Iron structures: Iron foundry and engineering works of August Borsig, Engineering works of Julius Conrad Freund, Royal Iron Foundry

- Reconstruction: ARGE Rohbau Neues Museum and numerous specialised companies

Key data

Location: Bodestraße 4, 10117 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period:

1841-59, shell 1841-45

1987-2009 securing and reconstruction

Structural design:

- Original building: Friedrich August Stüler, and Carl Wilhelm Hoffmann

- Reconstruction: Ingenieurgruppe Bauen (IGB)

Overall planning:

- Original building: Friedrich August Stüler with Ignaz Maria von Olfers

- Reconstruction: David Chipperfield Architects with Julian Harrap

Execution of construction work:

- Original construction: Numerous regional construction companies;

- Iron structures: Iron foundry and engineering works of August Borsig, Engineering works of Julius Conrad Freund, Royal Iron Foundry

- Reconstruction: ARGE Rohbau Neues Museum and numerous specialised companies