The Alexanderplatz around 1930: it gets cramped under the pavement

Extensive construction work began on Alexanderplatz in the mid-1920s. The first station shed, completed with the construction of the (elevated) “Stadtbahn” (“City Line”) in 1882, was renovated, and in addition to the already existing subway Stammbahn (“first line”, today: U2), two further subway lines were added: the “Nord-Süd-Bahn” ( "North-South Subway", today: U8) and a new line to Friedrichsfelde in the east (today: U5). Alexanderplatz became Berlin's largest and most complex transportation hub.

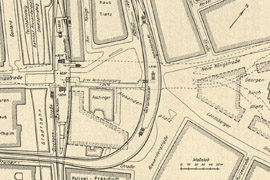

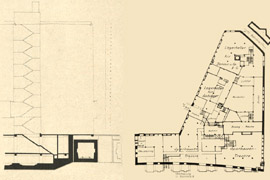

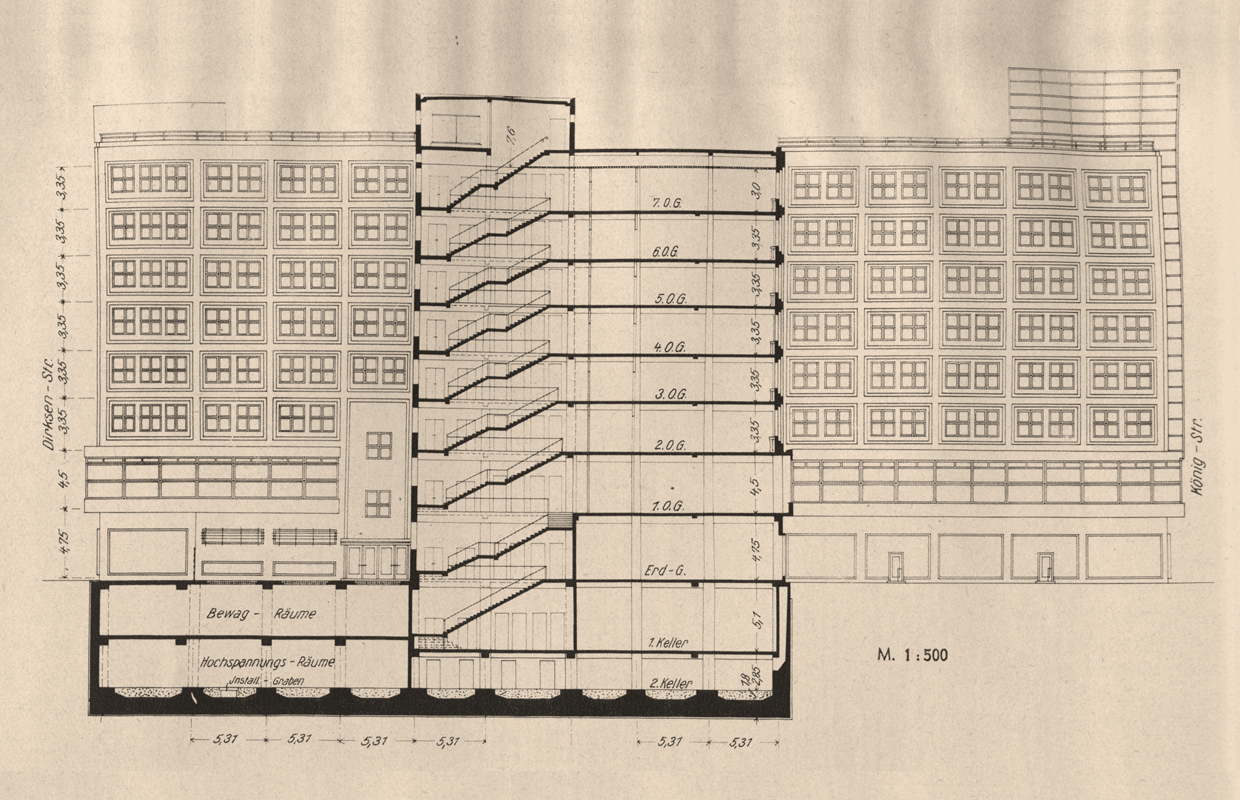

The plan from 1930 shows (still dashed) the layout of the future Alexanderhaus - sandwiched between the new "north-south subway" (left) and the existing "main line" (right). In the middle of the picture, the route of the future U5 can be seen above the Alexanderhaus (also still dashed).

The Alexanderplatz around 1930: it gets cramped under the pavement

Extensive construction work began on Alexanderplatz in the mid-1920s. The first station shed, completed with the construction of the (elevated) “Stadtbahn” (“City Line”) in 1882, was renovated, and in addition to the already existing subway Stammbahn (“first line”, today: U2), two further subway lines were added: the “Nord-Süd-Bahn” ( "North-South Subway", today: U8) and a new line to Friedrichsfelde in the east (today: U5). Alexanderplatz became Berlin's largest and most complex transportation hub.

The plan from 1930 shows (still dashed) the layout of the future Alexanderhaus - sandwiched between the new "north-south subway" (left) and the existing "main line" (right). In the middle of the picture, the route of the future U5 can be seen above the Alexanderhaus (also still dashed).

The 1928 competition: above the pavement, the plan is to change everything

The extensive civil engineering measures required the demolition of numerous existing buildings; this opened up the possibility of an urban redesign of the square. In 1928, the responsible "Verkehrs-AG" organized a competition on behalf of the magistrate; the basis was an alignment plan developed by city planning officer Martin Wagner.

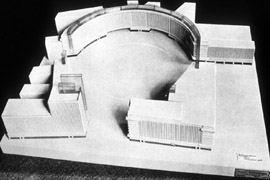

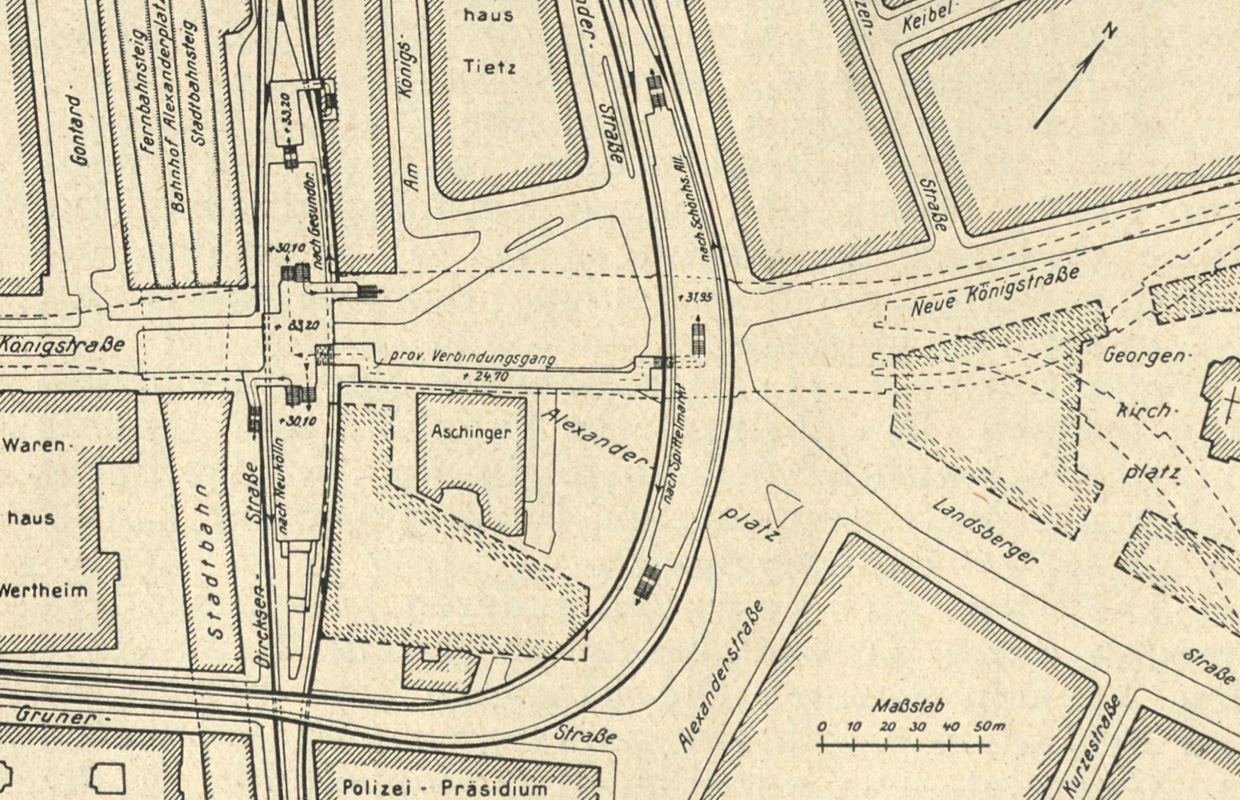

The design model by Peter Behrens clearly illustrates that the aim was not to make small-scale additions, but to radically redesign the square: the impressive large-scale form is opened up on the city rail side by a city gate flanked by head buildings.

The 1928 competition: everything should be different above the pavement

The extensive civil engineering measures required the demolition of numerous existing buildings; this opened up the possibility of an urban redesign of the square. In 1928, the responsible "Verkehrs-AG" organized a competition on behalf of the magistrate; the basis was an alignment plan developed by city planning officer Martin Wagner.

The design model by Peter Behrens clearly illustrates that the aim was not to make small-scale additions, but to radically redesign the square: the impressive large-scale form is opened up on the city rail side by a city gate flanked by head buildings.

Only the head buildings with the "gate" to the city railway are realized

The global economic crisis of 1929 prevented the implementation of the far-reaching ideas for the redesign of the area. It was only when an American consortium came on board in 1930 that at least parts of the project could be resumed.

Although only the second prize winner, Peter Behrens was awarded the planning contract for the two head-end buildings, though significantly lower than originally planned. The bird's eye view drawn in 1932 (now seen from the north-east) shows the gateway formed by the Alexander and Berolina Houses in front of the tram line.

Only the head buildings with the "gate" to the city railway are realized

The global economic crisis of 1929 prevented the implementation of the far-reaching ideas for the redesign of the area. It was only when an American consortium came on board in 1930 that at least parts of the project could be resumed.

Although only the second prize winner, Peter Behrens was awarded the planning contract for the two head-end buildings, though significantly lower than originally planned. The bird's eye view drawn in 1932 (now seen from the north-east) shows the gateway formed by the Alexander and Berolina Houses in front of the tram line.

The standard cross-section: four strings of columns in reinforced concrete on a solid floor slab

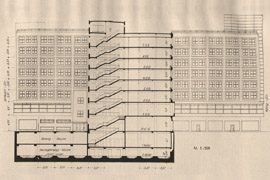

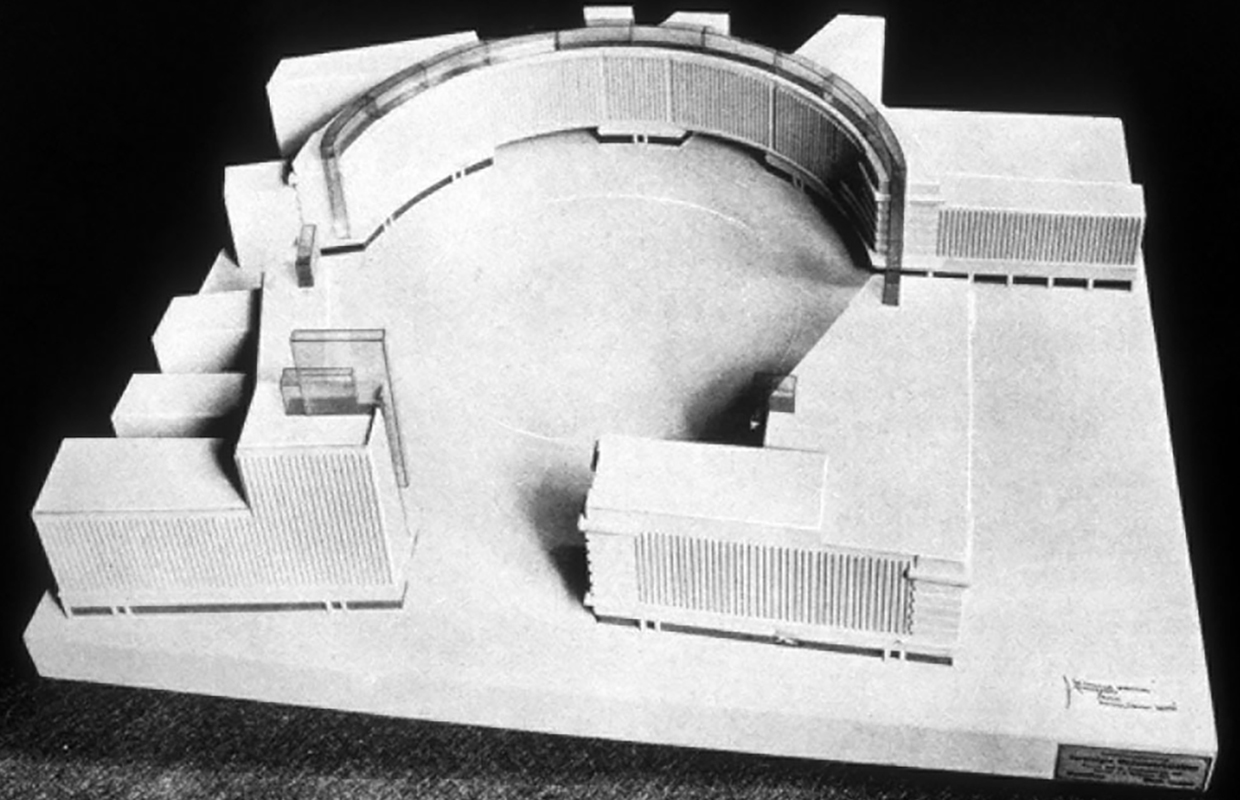

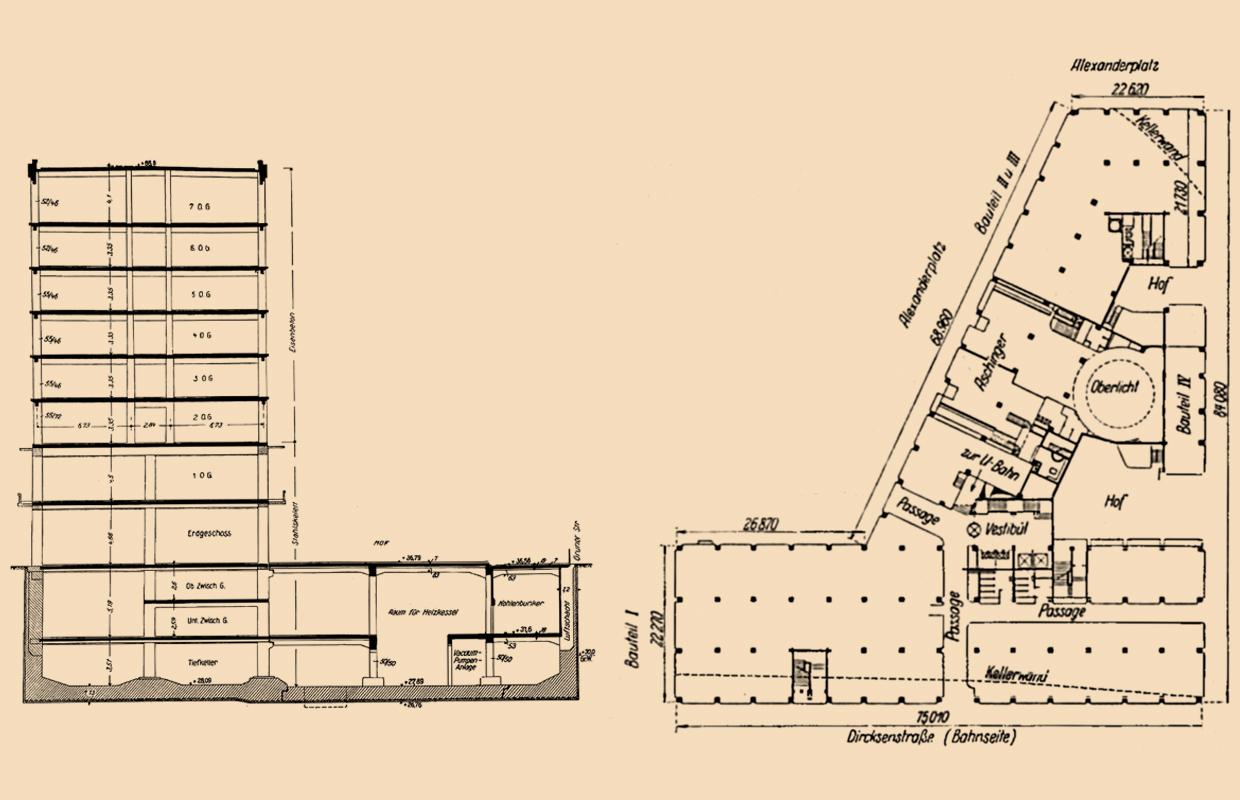

A four-column system was planned as the supporting framework for the ten-storey office and commercial building, in which the rooms are accessed via a central corridor. Comparative preliminary investigations showed that the reinforced concrete structure would be more cost-effective than a steel one.

The resulting standard cross-section with the reinforced concrete columns tapering upwards is shown here (next to one of the stairwells) in the sloping wing shortly before the transition to the city rail wing. The massive floor slab is remarkable. Located almost 10 m below street level and significantly reinforced at the load application points, it was part of a concrete trough that lay about 4 to 5 m deep in the groundwater after the temporary dewatering was completed.

The standard cross-section: four strings of columns in reinforced concrete on a solid floor slab

A four-column system was planned as the supporting framework for the ten-storey office and commercial building, in which the rooms are accessed via a central corridor. Comparative preliminary investigations showed that the reinforced concrete structure would be more cost-effective than a steel one.

The resulting standard cross-section with the reinforced concrete columns tapering upwards is shown here (next to one of the stairwells) in the sloping wing shortly before the transition to the city rail wing. The massive floor slab is remarkable. Located almost 10 m below street level and significantly reinforced at the load application points, it was part of a concrete trough that lay about 4 to 5 m deep in the groundwater after the temporary dewatering was completed.

In the large Aschinger restaurant: three instead of four pillars, steel instead of reinforced concrete

Significant areas in the sloping wing facing the square were intended for a traditional Berlin restaurant company, Aschinger AG, whose previous domicile on Alexanderplatz had to make way for the redesign.

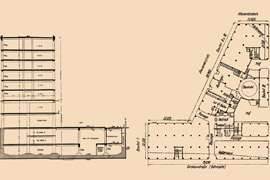

The plans for the new "Aschinger" in the Alexanderhaus envisaged large dining rooms on three floors, one above the other (from the second floor down to the first basement floor). As these were to be impaired as little as possible by internal columns, it was decided to arrange only one central column instead of two intermediate columns - the four-span structure became a three-span structure.

However, the larger spans could hardly be bridged with the otherwise favored reinforced concrete beams; the shear stresses were too great. As a result, the lower four storeys in the "Aschinger wing" were designed as a steel structure, in contrast to the rest of the building. The changed column positions are clearly visible in the floor plan and section.

In the large Aschinger restaurant: three instead of four pillars, steel instead of reinforced concrete

Significant areas in the sloping wing facing the square were intended for a traditional Berlin restaurant company, Aschinger AG, whose previous domicile on Alexanderplatz had to make way for the redesign.

The plans for the new "Aschinger" in the Alexanderhaus envisaged large dining rooms on three floors, one above the other (from the second floor down to the first basement floor). As these were to be impaired as little as possible by internal columns, it was decided to arrange only one central column instead of two intermediate columns - the four-span structure became a three-span structure.

However, the larger spans could hardly be bridged with the otherwise favored reinforced concrete beams; the shear stresses were too great. As a result, the lower four storeys in the "Aschinger wing" were designed as a steel structure, in contrast to the rest of the building. The changed column positions are clearly visible in the floor plan and section.

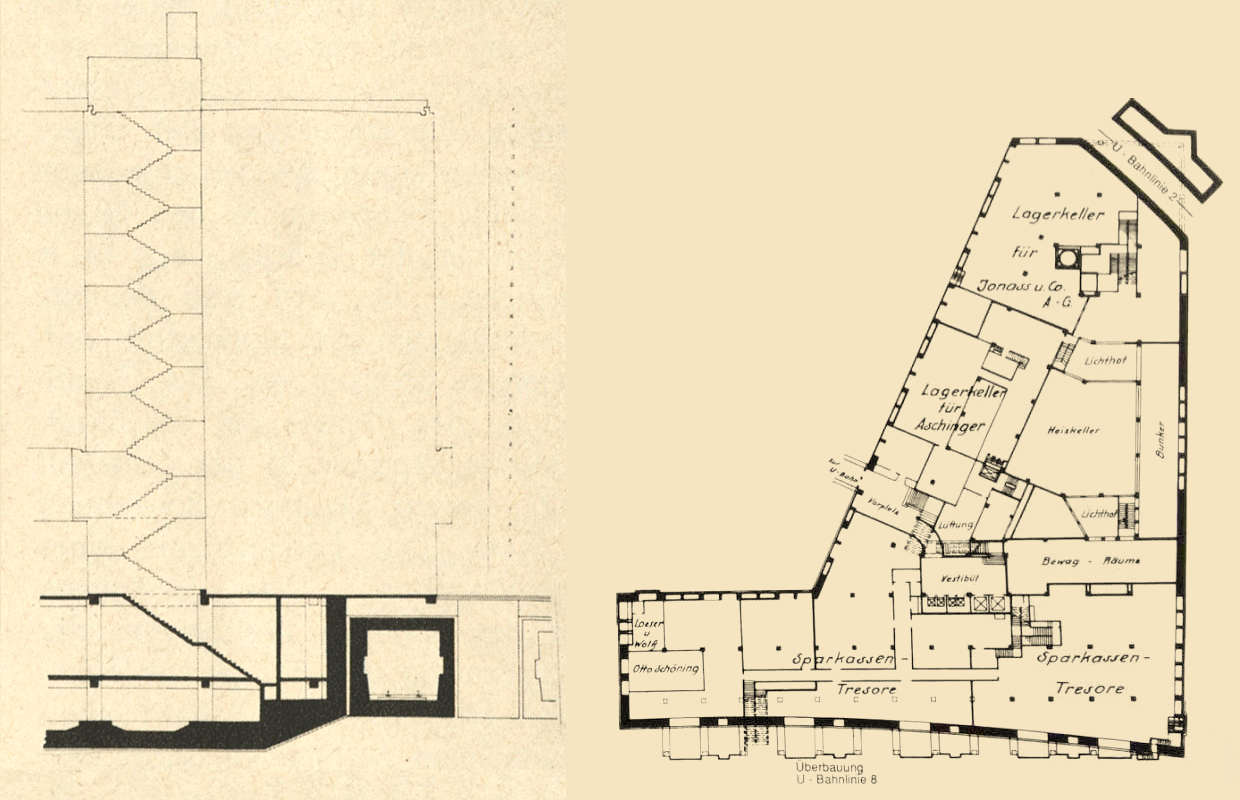

Eight storeys have to be supported above two subway tubes

The construction of the foundations for the structure between three levels of subway traffic in conjunction with complex dewatering were extremely difficult. It was not only necessary to place the loads on safe ground, but also to minimize the transmission of vibrations from the rail traffic as much as possible through targeted decoupling.

The superstructure of the two subway lines that cut under the construction site proved to be a particular challenge. The loads from no fewer than eight storeys above had to be absorbed in each case.

The area to be supported above the main line at the north-east corner was still relatively limited. Here, the engineers opted for a type of bridge made of densely staggered steel girders, which found their outer support on a newly created concrete pillar between the two tunnel tubes. On the Stadtbahn side, however, the Nord-Süd-Bahn, which was only built together with the Alexanderhaus, undercut the building along its entire length. As can be clearly seen in the schematic drawing, massive cantilever beams absorb the loads here.

Eight storeys have to be supported above two subway tubes

The construction of the foundations for the structure between three levels of subway traffic in conjunction with complex dewatering were extremely difficult. It was not only necessary to place the loads on safe ground, but also to minimize the transmission of vibrations from the rail traffic as much as possible through targeted decoupling.

The superstructure of the two subway lines that cut under the construction site proved to be a particular challenge. The loads from no fewer than eight storeys above had to be absorbed in each case.

The area to be supported above the main line at the north-east corner was still relatively limited. Here, the engineers opted for a type of bridge made of densely staggered steel girders, which found their outer support on a newly created concrete pillar between the two tunnel tubes. On the Stadtbahn side, however, the Nord-Süd-Bahn, which was only built together with the Alexanderhaus, undercut the building along its entire length. As can be clearly seen in the schematic drawing, massive cantilever beams absorb the loads here.

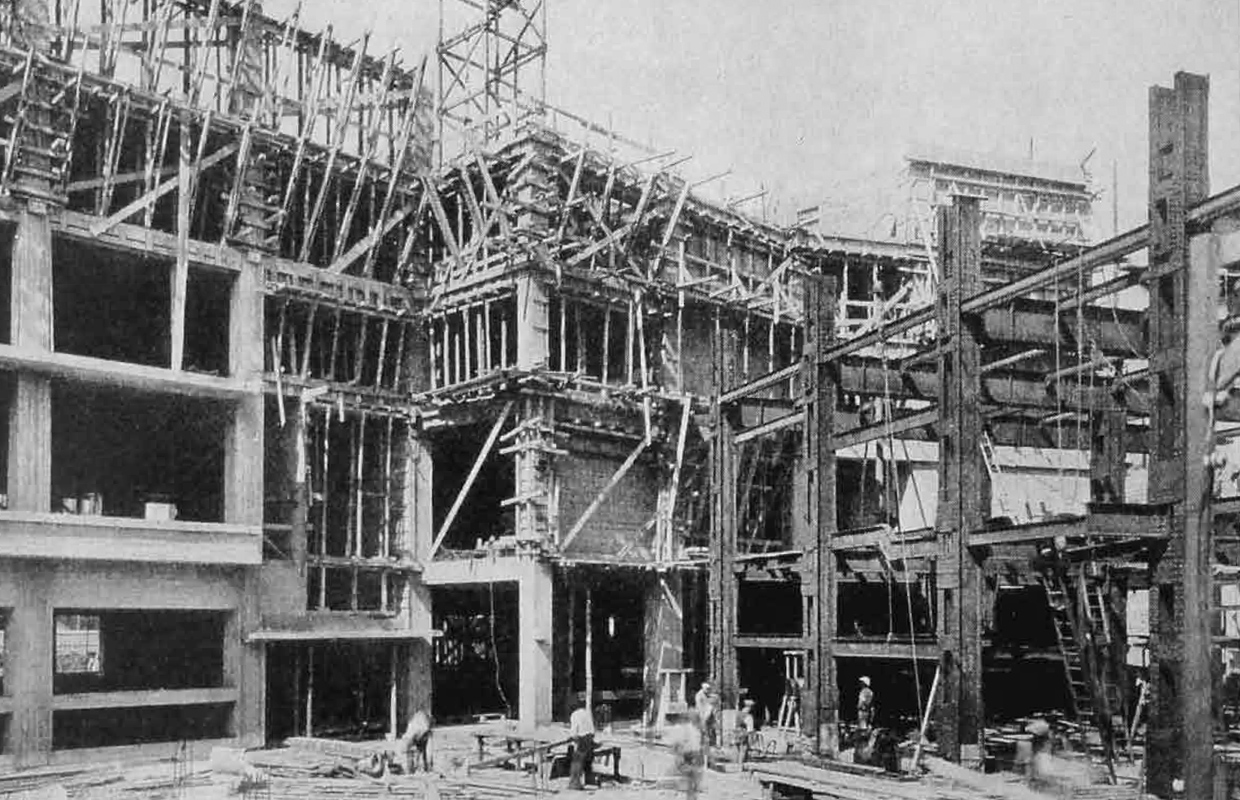

The steel framework in the excavation pit of the Aschinger wing at the beginning of 1932

In August 1930, pile driving work began on the construction pit. The fact that the foundations were not completed until a year later, in August 1931, underlines the complexity of the foundation.

In the photo from the basement floors in the Aschinger wing, the mighty tree trunks can be seen, which were led right through the steel construction to reinforce the excavation pit.

The steel framework in the excavation pit of the Aschinger wing at the beginning of 1932

In August 1930, pile driving work began on the construction pit. The fact that the foundations were not completed until a year later, in August 1931, underlines the complexity of the foundation.

In the photo from the basement floors in the Aschinger wing, the mighty tree trunks can be seen, which were led right through the steel construction to reinforce the excavation pit.

The Aschinger wing in steel, the wing close to the Stadtbahn in reinforced concrete

After that, things progressed very quickly. Construction of the shell only took a little more than another year: on December 23, 1932, the shell of the last component was approved. The photo shows the work on the junction between the reinforced concrete structure of the Stadtbahn wing and the steel structure on the ground floor of the Aschinger wing.

After completion, both Behrens buildings were rented out with great success. In 1937, the Berliner Sparkasse then acquired the Alexanderhaus from the US investors.

The Aschinger wing in steel, the wing close to the Stadtbahn in reinforced concrete

After that, things progressed very quickly. Construction of the shell only took a little more than another year: on December 23, 1932, the shell of the last component was approved. The photo shows the work on the junction between the reinforced concrete structure of the Stadtbahn wing and the steel structure on the ground floor of the Aschinger wing.

After completion, both Behrens buildings were rented out with great success. In 1937, the Berliner Sparkasse then acquired the Alexanderhaus from the US investors.

1945: An aerial mine tore the Jonas wing to shreds

The Allied bombing raids in February and April 1945 finally turned Alexanderplatz into a landscape of ruins. The Alexanderhaus was also badly hit. The picture shows the front left of the north-eastern front building, the Jonas wing, after it was largely destroyed by an aerial mine. Large parts of the ceilings and façade facing the square were hit directly by bombs; the building was also completely burnt out.

1945: An aerial mine tore the Jonas wing to shreds

The Allied bombing raids in February and April 1945 finally turned Alexanderplatz into a landscape of ruins. The Alexanderhaus was also badly hit. The picture shows the front left of the north-eastern front building, the Jonas wing, after it was largely destroyed by an aerial mine. Large parts of the ceilings and façade facing the square were hit directly by bombs; the building was also completely burnt out.

: Berliner Sparkasse, Haus der Weltjugend and a department store

The frame structures, however, were largely preserved. After an expert report in 1948 estimated the serious damage to the supporting structure at only 50%, reconstruction began in 1950 and was completed in 1952.

The "Berliner Sparkasse" (Berlin savings bank) moved into the Jonas wing, a department store of the GDR "Handelsorganisation (HO)" (trade organisation) was built in the wing facing the Stadtbahn, and the middle section became the "Haus der Weltjugend" (House of the youth of the world) on the occasion of the 2nd World Youth Games in 1951.

Berliner Sparkasse, Haus der Weltjugend and a department store

The frame structures, however, were largely preserved. After an expert report in 1948 estimated the serious damage to the supporting structure at only 50%, reconstruction began in 1950 and was completed in 1952.

The "Berliner Sparkasse" (Berlin savings bank) moved into the Jonas wing, a department store of the GDR "Handelsorganisation (HO)" (trade organisation) was built in the wing facing the Stadtbahn, and the middle section became the "Haus der Weltjugend" (House of the youth of the world) on the occasion of the 2nd World Youth Games in 1951.

The basic refurbishment 1993-95: Mostly a new building

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Alexanderhaus became the property of the Landesbank Berlin. New material investigations by the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM) and the Materials Testing Office of the State of Brandenburg (MPA) revealed fundamental structural safety deficits across the board, especially in the concrete structure. Nevertheless, complete demolition was out of the question: the two Behrens buildings, which had already been listed as monuments in 1977, were too prominent.

In 1993-95, the basic restoration was carried out according to plans by the architects Pysall, Stahrenberg & Partner. In many areas, however, it was equivalent to a new building: not only the top floor and the entire Jonas wing, but also all the ceilings were completely renewed. In order to at least preserve the historic reinforced concrete supports, they had to be reinforced with strong reinforced concrete sheathing.

However, it took a great deal of effort to restore the redesigned façade to its original appearance, taking into account today's thermal insulation requirements. This is probably why the client and architects were awarded the "Europa Nostra" European Heritage Prize in 1998.

The basic refurbishment 1993-95: Mostly a new building

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Alexanderhaus became the property of the Landesbank Berlin. New material investigations by the Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM) and the Materials Testing Office of the State of Brandenburg (MPA) revealed fundamental structural safety deficits across the board, especially in the concrete structure. Nevertheless, complete demolition was out of the question: the two Behrens buildings, which had already been listed as monuments in 1977, were too prominent.

In 1993-95, the basic restoration was carried out according to plans by the architects Pysall, Stahrenberg & Partner. In many areas, however, it was equivalent to a new building: not only the top floor and the entire Jonas wing, but also all the ceilings were completely renewed. In order to at least preserve the historic reinforced concrete supports, they had to be reinforced with strong reinforced concrete sheathing.

However, it took a great deal of effort to restore the redesigned façade to its original appearance, taking into account today's thermal insulation requirements. This is probably why the client and architects were awarded the "Europa Nostra" European Heritage Prize in 1998.

About the structural engineer

Due to the undercutting subway tubes, the structural design of the underground levels was in the hands of the engineers at Nord-Süd-Bahn AG.

However, Ferenc Domány (often referred to in German as Franz Domany), born in Hungary in 1899, was responsible for the structure above street level. Domány's fate is representative of the fate of many Jewish civil engineers in Berlin. In 1918/19, he initially studied engineering at the University of Technology in Budapest before transferring to the University of Technology in Berlin, where he graduated in 1923. In 1925, he founded his own engineering firm "Statik Domány" in Berlin, which was soon very successful, taking on the planning for large construction projects and working with prominent architects such as Behrens and Erich Mendelsohn (Columbushaus on Potsdamer Platz, 1931/32).

When the National Socialists came to power, the young success story came to an abrupt end. Domány returned to Budapest in 1933 and established a new planning office there. In 1939, however, he fled to Great Britain, where he committed suicide in Folkestone on September 9 at the age of 40.

About the structural engineer

Due to the undercutting subway tubes, the structural design of the underground levels was in the hands of the engineers at Nord-Süd-Bahn AG.

However, Ferenc Domány (often referred to in German as Franz Domany), born in Hungary in 1899, was responsible for the structure above street level. Domány's fate is representative of the fate of many Jewish civil engineers in Berlin. In 1918/19, he initially studied engineering at the University of Technology in Budapest before transferring to the University of Technology in Berlin, where he graduated in 1923. In 1925, he founded his own engineering firm "Statik Domány" in Berlin, which was soon very successful, taking on the planning for large construction projects and working with prominent architects such as Behrens and Erich Mendelsohn (Columbushaus on Potsdamer Platz, 1931/32).

When the National Socialists came to power, the young success story came to an abrupt end. Domány returned to Budapest in 1933 and established a new planning office there. In 1939, however, he fled to Great Britain, where he committed suicide in Folkestone on September 9 at the age of 40.

Key data of the original building

Location: Alexanderplatz 2, 10178 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period: 1930–32

Structural engineering:

- Basement floors: Nord-Süd-Bahn AG

- Floors from street level: Ferenc Domány

Overall planning: Peter Behrens

Execution of construction work:

- Reinforced concrete construction: Habermann & Guckes-Liebold, Grün & Bilfinger, Wayss & Freytag, Berlinische Bodengesellschaft, Deutsche Bauhütte

- Steel construction: Breest & Co., Krupp-Druckenmüller, Thyssen

Key data of the original building

Location: Alexanderplatz 2, 10178 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period: 1930–32

Structural engineering:

- Basement floors: Nord-Süd-Bahn AG

- Floors from street level: Ferenc Domány

Overall planning: Peter Behrens

Execution of construction work:

- Reinforced concrete construction: Habermann & Guckes-Liebold, Grün & Bilfinger, Wayss & Freytag, Berlinische Bodengesellschaft, Deutsche Bauhütte

- Steel construction: Breest & Co., Krupp-Druckenmüller, Thyssen