Text vorlesen lassen

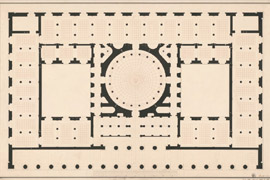

Schinkel's design from 1823: Pantheon and colonnaded hall

Making the Royal Art Collections accessible to the public was anything but a matter of course in Prussia and, in terms of typology, a building task that was still without precedent. It is therefore not surprising that the initial plans from 1816 onwards only envisaged the conversion of a wing of the Royal Academy on Universitätsstraße.

In 1822, however, the idea of an independent new building on the Lustgarten matured. At the end of the year, Schinkel developed initial designs on behalf of Friedrich Willhelm III. More precise site investigations subsequently led, among other things, to a shift in the building site by around 10 m to the east. The plans were fleshed out over the course of the summer and finally came to completion in September 1823.

A strictly structured four-winged complex with a plinth and two main storeys is grouped around two inner courtyards and the Pantheon-citation of a dome-crowned rotunda. The most powerful gesture, however, is the striking and almost archaic portico that dominates the entire front facing the pleasure garden.

Schinkel's design from 1823: Pantheon and colonnaded hall

Making the Royal Art Collections accessible to the public was anything but a matter of course in Prussia and, in terms of typology, a building task that was still without precedent. It is therefore not surprising that the initial plans from 1816 onwards only envisaged the conversion of a wing of the Royal Academy on Universitätsstraße.

In 1822, however, the idea of an independent new building on the Lustgarten matured. At the end of the year, Schinkel developed initial designs on behalf of Friedrich Willhelm III. More precise site investigations subsequently led, among other things, to a shift in the building site by around 10 m to the east. The plans were fleshed out over the course of the summer and finally came to completion in September 1823.

A strictly structured four-winged complex with a plinth and two main storeys is grouped around two inner courtyards and the Pantheon-citation of a dome-crowned rotunda. The most powerful gesture, however, is the striking and almost archaic portico that dominates the entire front facing the pleasure garden.

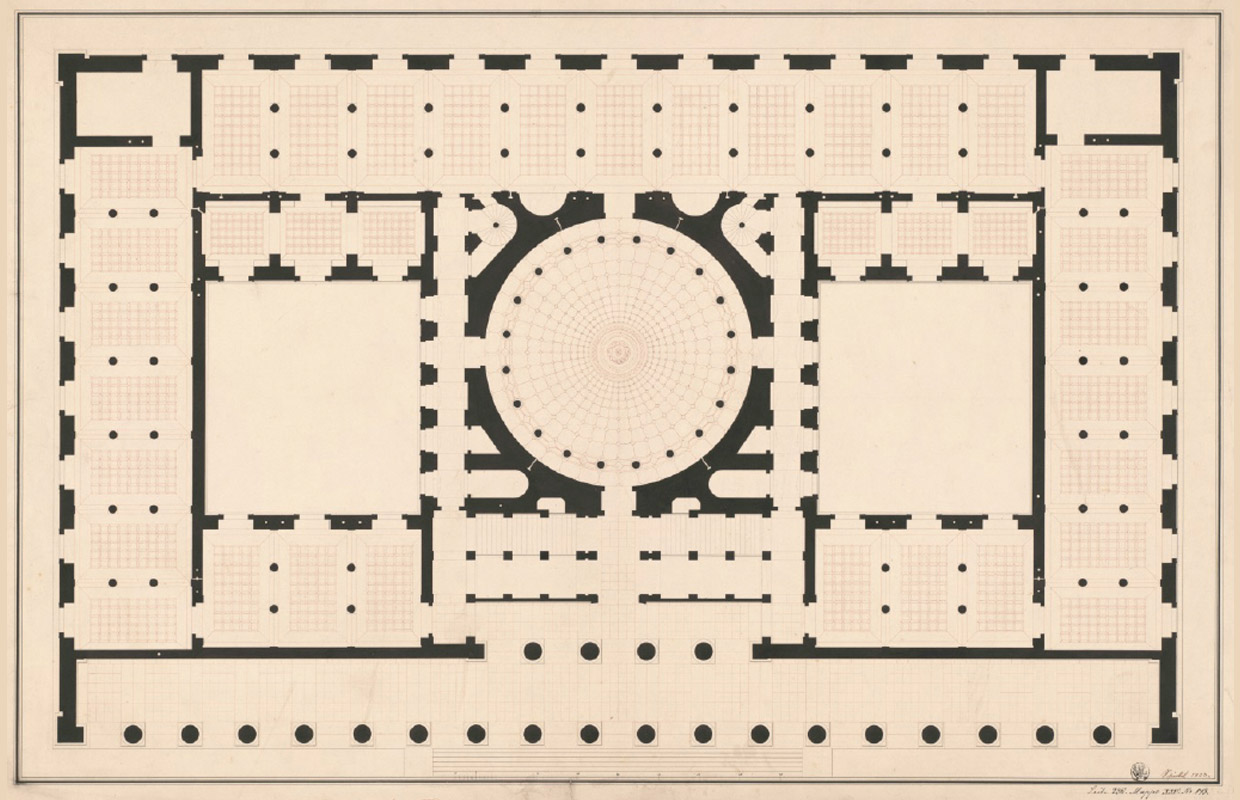

The roof structure above the rotunda in the 1823 design

The first design for a "large window", which was to cover the almost nine-metre wide opening at the top of the dome, was created as early as 1823. With this iron construction, which was still unknown in Prussia, Schinkel referred to French models, which he had already seen during his first stay in Paris in 1804/05.

A drawing signed "Schinkel 1823" reflects the planning status. In an impressive condensation, it shows different heights of the wooden roof structure in the four quadrants of the roof space surrounding the dome. The filigree supporting structure of the planned glass and iron roof rests on the top layer in the centre.

The roof structure above the rotunda in the 1823 design

The first design for a "large window", which was to cover the almost nine-metre wide opening at the top of the dome, was created as early as 1823. With this iron construction, which was still unknown in Prussia, Schinkel referred to French models, which he had already seen during his first stay in Paris in 1804/05.

A drawing signed "Schinkel 1823" reflects the planning status. In an impressive condensation, it shows different heights of the wooden roof structure in the four quadrants of the roof space surrounding the dome. The filigree supporting structure of the planned glass and iron roof rests on the top layer in the centre.

Work on the pile foundations begins in July 1824

The development of the construction site had already required considerable preparatory work on the watercourses defining the terrain since the summer of 1823. Excavation of the building pit began in February 1824, and in July of that year the pile foundations could be started. The dimensions of these piles were still completely unknown, so they were planned and monitored all the more carefully and a total of 3,053 piles were driven into the subsoil, which was interspersed with foul-silt lenses. The foundation grid was completed over the course of the winter.

The pile plan of the eastern half shown here was apparently prepared as an execution plan and then supplemented during the driving of the piles with information on the actual execution, including notes on additional piles placed.

The spring of 1825 saw the start of the masonry work. Schinkel had various tests carried out with different types of mortar. As a result, "English Portland cement" was used for the first time in Prussia instead of the usual lime mortar, not only in the plinth storey, but also in parts of the dome and the ceiling above the vestibule. The topping-out ceremony was held in November 1826.

Work on the pile foundations begins in July 1824

The development of the construction site had already required considerable preparatory work on the watercourses defining the terrain since the summer of 1823. Excavation of the building pit began in February 1824, and in July of that year the pile foundations could be started. The dimensions of these piles were still completely unknown, so they were planned and monitored all the more carefully and a total of 3,053 piles were driven into the subsoil, which was interspersed with foul-silt lenses. The foundation grid was completed over the course of the winter.

The pile plan shown here was apparently prepared as an execution plan and then supplemented during the driving of the piles with information on the actual execution, including notes on additional piles placed.

The spring of 1825 saw the start of the masonry work. Schinkel had various tests carried out with different types of mortar. As a result, "English Portland cement" was used for the first time in Prussia instead of the usual lime mortar, not only in the plinth storey, but also in parts of the dome and the ceiling above the vestibule. The topping-out ceremony was held in November 1826.

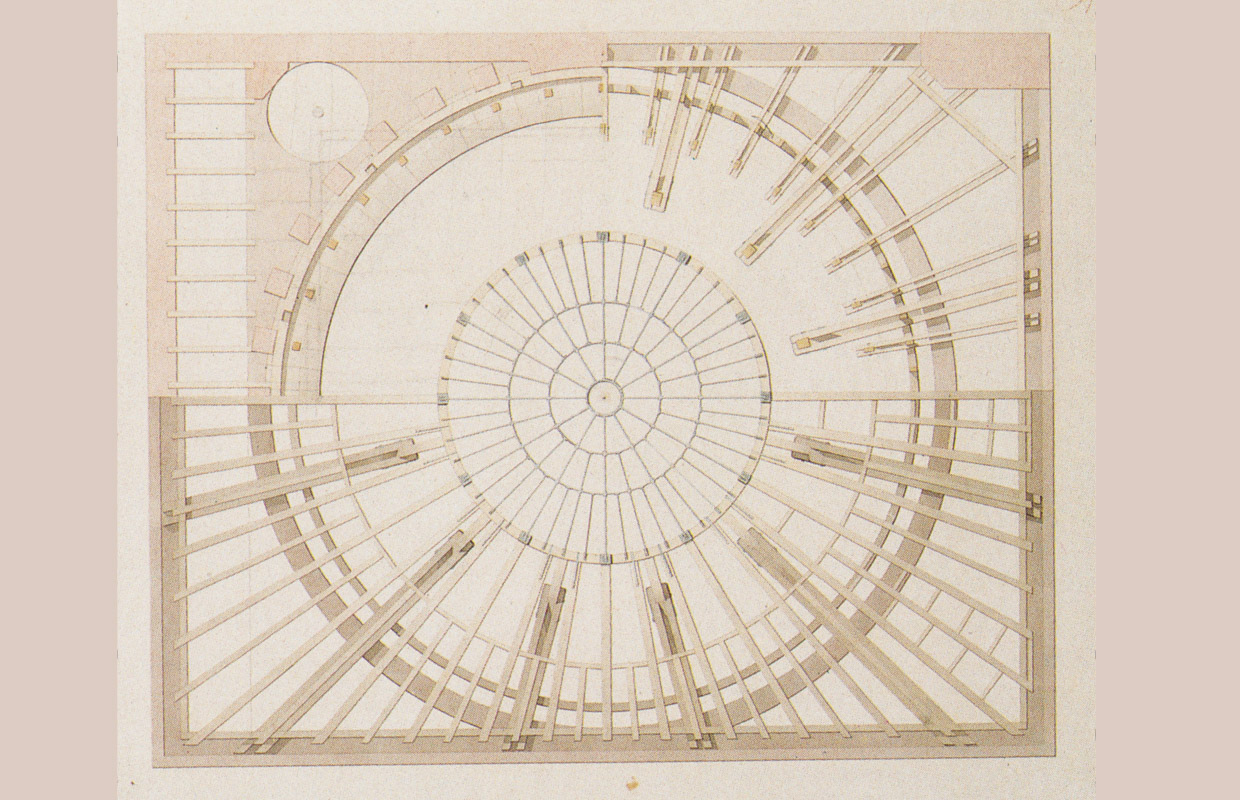

Innovative in Prussia - the iron roof structure above the skylight

The detailing and construction of the glass and iron roof took place in 1827. The final design differed significantly not only from the initial considerations in 1823, but also underwent significant changes in the course of the shop drawing.

For example, the iron supporting structure, which spanned around 9 metres, was no longer supported on cantilevered beams of the wooden roof, but on cast-iron posts on the brick dome. The corresponding planning status shown here, which dates back to 1827, still envisaged twelve elevated main ribs. In the end, a variant with 20 main ribs and some modified details was realised.

This optimisation of materials and production technology was carried out in close consultation with Franz Anton Egell's iron foundry and engineering company. In autumn, the completed work of art made of cast and wrought iron was completely pre-assembled on a trial basis and then transported to the construction site.

Innovative in Prussia - the iron roof structure above the skylight

The detailing and construction of the glass and iron roof took place in 1827. The final design differed significantly not only from the initial considerations in 1823, but also underwent significant changes in the course of the shop drawing.

For example, the iron supporting structure, which spanned around 9 metres, was no longer supported on cantilevered beams of the wooden roof, but on cast-iron posts on the brick dome. The corresponding planning status shown here, which dates back to 1827, still envisaged twelve elevated main ribs. In the end, a variant with 20 main ribs and some modified details was realised.

This optimisation of materials and production technology was carried out in close consultation with Franz Anton Egell's iron foundry and engineering company. In autumn, the completed work of art made of cast and wrought iron was completely pre-assembled on a trial basis and then transported to the construction site.

The museum was opened on the king's 60th birthday in 1830

The building was completed in 1828. However, the interior design and furnishings took more than two years before the "Königliches Museum am Lustgarten" officially opened its doors on 3 August 1830, the king's 60th birthday.

The famous drawing published by Schinkel in 1831 in his "Collection of Architectonic Designs" gives an impression of the atmosphere at the time. The "Perspective view from the gallery of the museum's main staircase" is, of course, more than just an architectural depiction - it is the illustrated programme of a bourgeois educational ideal that manifested itself anew and confidently at this location in the context of the city palace (monarchy), cathedral (church) and armoury (military) as a fourth pole.

The museum was opened on the king's 60th birthday in 1830

The building was completed in 1828. However, the interior design and furnishings took more than two years before the "Königliches Museum am Lustgarten" officially opened its doors on 3 August 1830, the king's 60th birthday.

The famous drawing published by Schinkel in 1831 in his "Collection of Architectonic Designs" gives an impression of the atmosphere at the time. The "Perspective view from the gallery of the museum's main staircase" is, of course, more than just an architectural depiction - it is the illustrated programme of a bourgeois educational ideal that manifested itself anew and confidently at this location in the context of the city palace (monarchy), cathedral (church) and armoury (military) as a fourth pole.

The Altes Museum around 1900 - essentially unchanged

In the 1870s, minor alterations were made to the skylight rooms, which were given iron roof structures. Essentially, however, the exterior of the building, now called the Altes Museum after the construction of the Neues Museum in the 1840s, remained largely unchanged until its destruction in the Second World War.

The colourised photograph was taken around 1900. The splendidly designed pleasure garden is dominated by the equestrian statue of emperor Wilhelm II, and the (Old) Nationalgalerie can be seen in the background alongside the Neues Museum. To the left of the Altes Museum is the residence of the General Tax Director, also built according to Schinkel's design in the early 1830s; it was demolished in 1937 due to considerable structural damage.

The Altes Museum around 1900 - essentially unchanged

In the 1870s, minor alterations were made to the skylight rooms, which were given iron roof structures. Essentially, however, the exterior of the building, now called the Altes Museum after the construction of the Neues Museum in the 1840s, remained largely unchanged until its destruction in the Second World War.

The colourised photograph was taken around 1900. The splendidly designed pleasure garden is dominated by the equestrian statue of emperor Wilhelm II, and the (Old) Nationalgalerie can be seen in the background alongside the Neues Museum. To the left of the Altes Museum is the residence of the General Tax Director, also built according to Schinkel's design in the early 1830s; it was demolished in 1937 due to considerable structural damage.

The 2nd World War leaves behind a burnt-out ruin

At the beginning of the Second World War, all the buildings on Museum Island were closed and the collections moved to sheltered locations. As early as 1941, an aerial bomb hits the north wing of the Altes Museum for the first time, and in December 1943 another one ruins the building in the same place, now down to the foundations. In May 1944, a fire destroys the old roof truss, among other things. Shortly before the end of the war, 25 direct hits fall on the Museum Island alone in the heavy daylight raid of 3 February 1945, which set entire streets in Berlin-Mitte on fire. The final blow came, probably on 30 April (... according to another source, however, not until 8 May), when an ammunition wagon or similar explodes right next to the Altes Museum - what was left of Schinkel's masterpiece now is completely burnt out. The following morning, the first Soviet soldiers appear on Museum Island.

The photo by the famous Soviet war photographer Timofej Melnik (1911-1985) shows a parade of the 32nd Rifle Corps of the 5th Shock Army in front of the columned front of the Altes Museum on 4 May 1945.

The 2nd World War leaves behind a burnt-out ruin

At the beginning of the Second World War, all the buildings on Museum Island were closed and the collections moved to sheltered locations. As early as 1941, an aerial bomb hits the north wing of the Altes Museum for the first time, and in December 1943 another one ruins the building in the same place, now down to the foundations. In May 1944, a fire destroys the old roof truss, among other things. Shortly before the end of the war, 25 direct hits fall on the Museum Island alone in the heavy daylight raid of 3 February 1945, which set entire streets in Berlin-Mitte on fire. The final blow came, probably on 30 April (... according to another source, however, not until 8 May), when an ammunition wagon or similar explodes right next to the Altes Museum - what was left of Schinkel's masterpiece now is completely burnt out. The following morning, the first Soviet soldiers appear on Museum Island.

The photo by the famous Soviet war photographer Timofej Melnik (1911-1985) shows a parade of the 32nd Rifle Corps of the 5th Shock Army in front of the columned front of the Altes Museum on 4 May 1945.

1953/54 The rotunda is given a roof again

The first modest safety measures were taken in 1951. These led to the construction of a new roof over the rotunda in 1953/54, which is apparently still in use today.

In 1958, the now officially approved reconstruction began, which fundamentally changed the interior with new room layouts and the installation of solid ceilings. In 1966, the building was reopened as the Museum of Contemporary Art of the GDR.

1953/54 The rotunda is given a roof again

The first modest safety measures were taken in 1951. These led to the construction of a new roof over the rotunda in 1953/54, which is apparently still in use today.

In 1958, the now officially approved reconstruction began, which fundamentally changed the interior with new room layouts and the installation of solid ceilings. In 1966, the building was reopened as the Museum of Contemporary Art of the GDR.

Schinkel's iron roof structure for the skylight has been preserved

The original construction of the iron roof structure above the skylight of the rotunda has largely been preserved. However, the smaller intermediate ribs, which were originally inserted between the base and third ring, are missing.

During reconstruction, they were replaced by steel rafters made from square profiles. The latter were also used as elevations on the preserved main ribs. As a result, a total of 40 new square profiles now support the glazing, which is slightly flatter than before.

From today's perspective, it is astonishing that the new steel profiles were welded to the historic structural elements during the course of the renovation - actually a no-go when dealing with iron materials from the early 19th century!

Schinkel's iron roof structure for the skylight has been preserved

The original construction of the iron roof structure above the skylight of the rotunda has largely been preserved. However, the smaller intermediate ribs, which were originally inserted between the base and third ring, are missing.

During reconstruction, they were replaced by steel rafters made from square profiles. The latter were also used as elevations on the preserved main ribs. As a result, a total of 40 new square profiles now support the glazing, which is slightly flatter than before.

From today's perspective, it is astonishing that the new steel profiles were welded to the historic structural elements during the course of the renovation - actually a no-go when dealing with iron materials from the early 19th century!

The glazing of the staircase hall - nothing is more permanent than a temporary solution

In 1991, a Rembrandt exhibition led to an intervention with serious consequences: large-format glass panes were installed between the columns in front of the staircase hall with the aim of creating a climate-protected connection between the two wings of the building.

Both the State Monuments Office and the State Monuments Council had vigorously opposed the intervention. The reality proved them right in two respects: The intervention fundamentally changed both the external appearance and the internal perception of the vestibule and - although dubbed a temporary measure - has not been dismantled to this day.

As early as 1998, a competition was organised for the general refurbishment of the Altes Museum. The winning design has still not been realised. Only smaller measures such as the renovation of the open staircase (2007) and the coffered ceiling of the rotunda (2009) have been brought forward. It is to be hoped that a better solution than the scandalous full glazing for the air-conditioning requirements will be found in the course of the overall refurbishment.

The glazing of the staircase hall - nothing is more permanent than a temporary solution

In 1991, a Rembrandt exhibition led to an intervention with serious consequences: large-format glass panes were installed between the columns in front of the staircase hall with the aim of creating a climate-protected connection between the two wings of the building.

Both the State Monuments Office and the State Monuments Council had vigorously opposed the intervention. The reality proved them right in two respects: The intervention fundamentally changed both the external appearance and the internal perception of the vestibule and - although dubbed a temporary measure - has not been dismantled to this day.

As early as 1998, a competition was organised for the general refurbishment of the Altes Museum. The winning design has still not been realised. Only smaller measures such as the renovation of the open staircase (2007) and the coffered ceiling of the rotunda (2009) have been brought forward. It is to be hoped that a better solution than the scandalous full glazing for the air-conditioning requirements will be found in the course of the overall refurbishment.

It is the dust cover that turns Schinkel's work of art into a hidden structure

Although on a smaller scale, another glazing that was added earlier is just as annoying.

Schinkel had probably deliberately left the filigree glass and iron construction at the apex of the rotunda dome visible to everyone. Just as in the scale-setting Roman model, the barely disturbed open view went into the infinity of the firmament - conveyed by contemporary high technology as a promise of Prussia's future. The supporting structure only became a hidden structure when a dust protection was added during reconstruction, which today prevents an open view upwards and also gives a simply false impression of the structure above with its translucent ribs.

A solution to this nuisance should also be found in the course of the upcoming basic restoration, which opens up the opaion again and recovers Schinkel's idea of ennobling the construction.

It is the dust cover that turns Schinkel's work of art into a hidden structure

Although on a smaller scale, another glazing that was added earlier is just as annoying.

Schinkel had probably deliberately left the filigree glass and iron construction at the apex of the rotunda dome visible to everyone. Just as in the scale-setting Roman model, the barely disturbed open view went into the infinity of the firmament - conveyed by contemporary high technology as a promise of Prussia's future. The supporting structure only became a hidden structure when a dust protection was added during reconstruction, which today prevents an open view upwards and also gives a simply false impression of the structure above with its translucent ribs.

A solution to this nuisance should also be found in the course of the upcoming basic restoration, which opens up the opaion again and recovers Schinkel's idea of ennobling the construction.

About the structural engineer

It is well known that Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841) considered architecture and construction to be two sides of the same art of building. It is not surprising that he also worked intensively on the structural realisation and details of the Royal Museum.

The chief construction manager Johann Carl Ludwig Schmid (1780-1849) was probably primarily responsible for the economic and logistical management of the large-scale project. The still young Gottlieb Ernst Kreye (*around 1800-1863 or -64), who drew up the more than 60 working drawings for the museum building, was hardly of any great importance for the construction design. However, the importance of Georg Heinrich Bürde (1796-1865) seems to have been more significant: As site manager, he was also responsible for all questions of structural realisation, as was customary at the time; this is proven to be particularly true for the detailing of the iron structure above the rotunda.

As a result, Bürde and Schinkel can be regarded today as the "structural engineers" of the Altes Museum.

About the structural engineer

It is well known that Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841) considered architecture and construction to be two sides of the same art of building. It is not surprising that he also worked intensively on the structural realisation and details of the Royal Museum.

The chief construction manager Johann Carl Ludwig Schmid (1780-1849) was probably primarily responsible for the economic and logistical management of the large-scale project. The still young Gottlieb Ernst Kreye (*around 1800-1863 or -64), who drew up the more than 60 working drawings for the museum building, was hardly of any great importance for the construction design. However, the importance of Georg Heinrich Bürde (1796-1865) seems to have been more significant: As site manager, he was also responsible for all questions of structural realisation, as was customary at the time; this is proven to be particularly true for the detailing of the iron structure above the rotunda.

As a result, Bürde and Schinkel can be regarded today as the "structural engineers" of the Altes Museum.

The importance of the ironworker

The extent to which Franz Anton Egells (1788-1854), who was born in Rheine in Westphalia, also (co-) planned and influenced the detailing of the glass and iron roof or rather limited himself to the neat execution remains to be seen. Just a few years later, Egells once again worked with Schinkel on another spectacular project, the construction of the filigree rotating ribbed dome (1834) of the Royal Observatory.

The "Eisengießerei und Maschinenbauanstalt", which he founded on Chausseestraße in 1822, shortly before construction of the museum began, is considered in retrospect to be one of the nuclei of Berlin and Prussian iron and mechanical engineering. Renowned iron and machine builders of the "second generation" learned their trade here before founding their own companies in the boom of industrialization - all before August Borsig (1804-1854), who was to shape Berlin and Prussian iron construction like no other in the 1840s.

The importance of the ironworker

The extent to which Franz Anton Egells (1788-1854), who was born in Rheine in Westphalia, also (co-) planned and influenced the detailing of the glass and iron roof or rather limited himself to the neat execution remains to be seen. Just a few years later, Egells once again worked with Schinkel on another spectacular project, the construction of the filigree rotating ribbed dome (1834) of the Royal Observatory.

The "Eisengießerei und Maschinenbauanstalt", which he founded on Chausseestraße in 1822, shortly before construction of the museum began, is considered in retrospect to be one of the nuclei of Berlin and Prussian iron and mechanical engineering. Renowned iron and machine builders of the "second generation" learned their trade here before founding their own companies in the boom of industrialization - all before August Borsig (1804-1854), who was to shape Berlin and Prussian iron construction like no other in the 1840s.

Key data

Location: Bodestraße 1–3, 10178 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period:

- 1824-28, erection of the glass and iron roof over the rotunda in 1827

- 1958-66, reconstruction with fundamental changes to the interior

Overall planning: Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Site management and structural detailing: Georg Heinrich Bürde

Execution of construction work:

- Masonry work: Awarded in lots to numerous small companies

- Iron construction: Franz Anton Egells’ iron foundry and engineering works

Key data

Location: Bodestraße 1–3, 10178 Berlin-Mitte

Construction period:

- 1824-28, erection of the glass and iron roof over the rotunda in 1827

- 1958-66, reconstruction with fundamental changes to the interior

Overall planning: Karl Friedrich Schinkel

Site management and structural detailing: Georg Heinrich Bürde

Execution of construction work:

- Masonry work: Awarded in lots to numerous small companies

- Iron construction: Franz Anton Egells’ iron foundry and engineering works